Its Aims and Organisation

Since the beginning of broadcasting, the broadcasting authorities have been aware of the value that lies in a close collaboration on the international plane. The imperative reasons acting in favour of such collaboration were:

- the very nature of radio waves, which ignore national frontiers;

- the similarity of the problems arising from the operation of broadcasting services in the different countries;

- the need to organise programme exchanges between broadcasting organisations;

- the complexity and interdependence of the problems posed from the technical, artistic and legal points of view, which called for a close collaboration between the engineers, programme staff and jurists of the different countries.

These reasons brought about the formation of a specialised international organisation whose activities include all aspects of broadcasting.

This organisation was, originally, the International Broadcasting Union (I.B.U.) which was formed at Geneva in 1925.

Since 1950, the European Broadcasting Union (E.B.U.) which succeeded the I.B.U., has fulfilled this task.

What is the E.B.U. ?

In law the European Broadcasting Union is a non-governmental international organisation whose object is to take care of the interests of organisations operating broadcasting services.

It is a private association, with no commercial aim, although it is an association of operating organisations.

The term “broadcasting service” should be taken in its most general sense, covering both sound and television broadcasting. It is, therefore, in this general sense that the term “broadcasting” should herein be understood, as it appears in the title of the Union, which includes both sound broadcasting and television organisations.

In French, the Union is called “Union Européenne de Radiodiffusion”, it being known in that language by the initials “U.E.R.” The two working languages of the Union are, in effect, French and English.

Professionally In the terms of its statutes, the aims of the European Broadcasting Union are:

- to support in every domain the interest of its affiliated broadcasting organisations and to establish relations with other broadcasting organisations;

- to promote all measures designed to assist the development of broadcasting in all its forms;

- to seek the solution, by means of international cooperation, of any differences that may arise;

- to use its best endeavours to ensure that all its Members respect the provisions of international agreements relating to all aspects of broadcasting

This enumeration of general principles guiding the E.B.U. in the orientation of its work permits judging the scope and diversity of its objectives, as will be shown in the description of its activities.

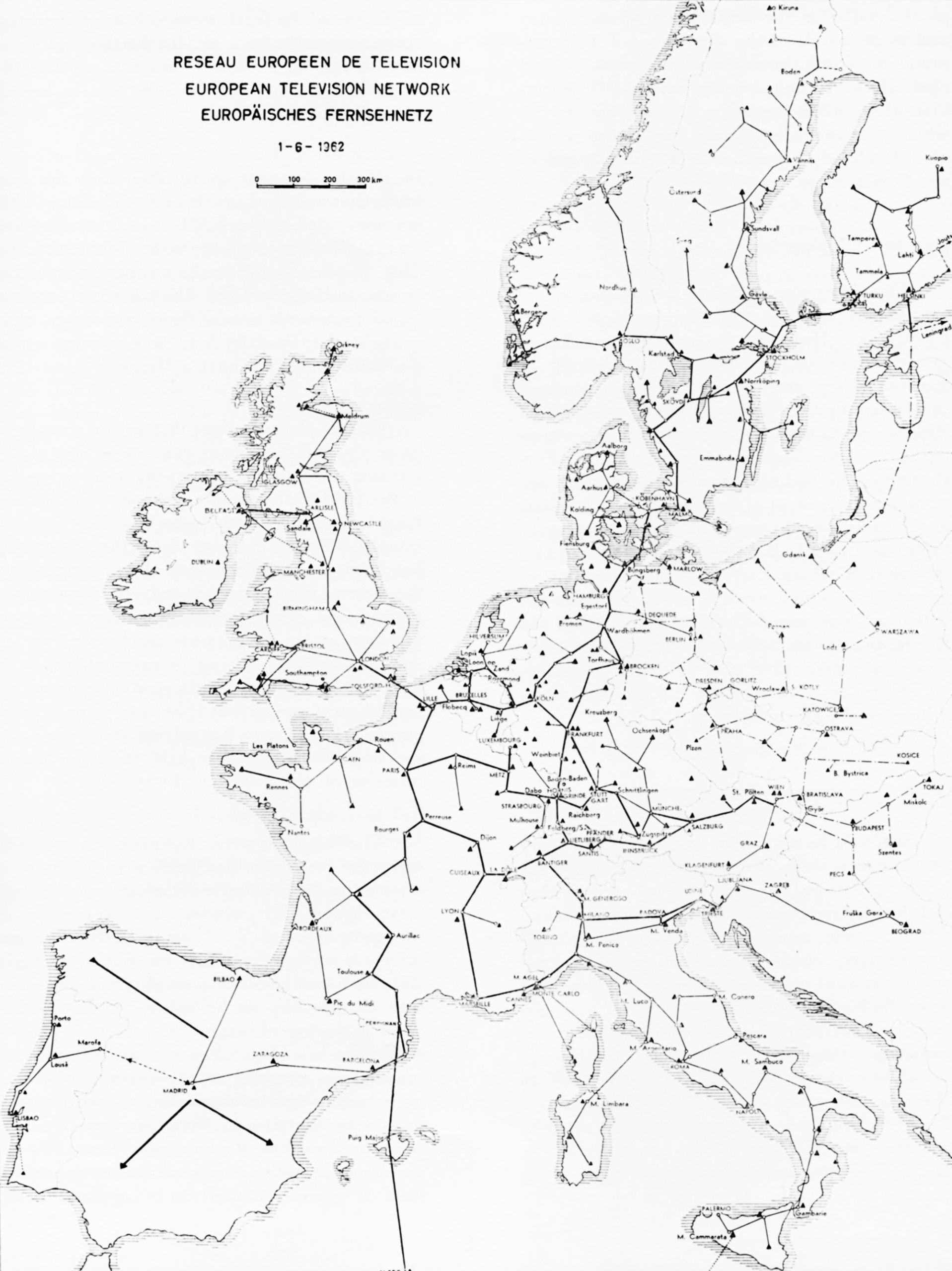

Geographically As its name indicates, the activity of the E.B.U. covers in the first place the countries of Europe, as well as the countries bordering on the Mediterranean, which, in the terms of the Conventions of the International Telecommunication Union (I.T.U.), are part of the “European Broadcasting Area”.

The activities of the E.B.U., however, extend outside Europe, a large number of extra-European broadcasting organisations having associated themselves with its work or achievements.

Thus the E.B.U. includes sound and television broadcasting organisations throughout the world, such organisations belonging to countries that are either members or associate members of the I.T.U.

- Only organisations within the “European Broadcasting Area” may belong to the E.B.U. as Active Members, that is to say, as members enjoying full rights.*

- Organisations in other parts of the world can belong to the E.B.U. only as Associate Members.

On 30th June, 1962, there were twenty-seven Active Members, in twenty-five countries:

Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany (Federal Republic), Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Jugoslavia, Lebanon, Luxembourg, Monaco, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey, United Kingdom, Vatican City.

On the same date, there were twenty-four Associate Members, all, except one, outside the European Broadcasting Area, in seventeen countries:

Australia, Burma, Canada, Ceylon, Congo (Leopoldville), Dahomey, Ghana, Haiti, Japan, Morocco, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, Rhodesia and Nyasaland, South Africa, United States of America, Upper Volta.

The map reproduced above gives an idea of the geographical distribution of the E.B.U.’s Members and Associate Members, the full alphabetical list of whom is shown in the table. It also shows that, thanks to the E.B.U., cooperation in the field of broadcasting has become a reality from one end of the world to the other.

* Nevertheless, by derogation of this principle, an organisation within the European Broadcasting Area, other than those of Continental Europe, Iceland, Ireland and the United Kingdom, may ask for admission as Associate Member instead of Active Member.

How does the E.B.U. work?

The general policy of the Union, the policy of decision in the orientation of its work, the determination of the programme of its activities, the admission or withdrawal of affiliation of E.B.U. Members, are dealt with by the General Assembly and the Administrative Council, whose activity concentrates on periodical meetings. The preparation of the decisions of these assemblies is the duty of the Union’s Committees, who play a consultative part, and of the permanent, executive, services.

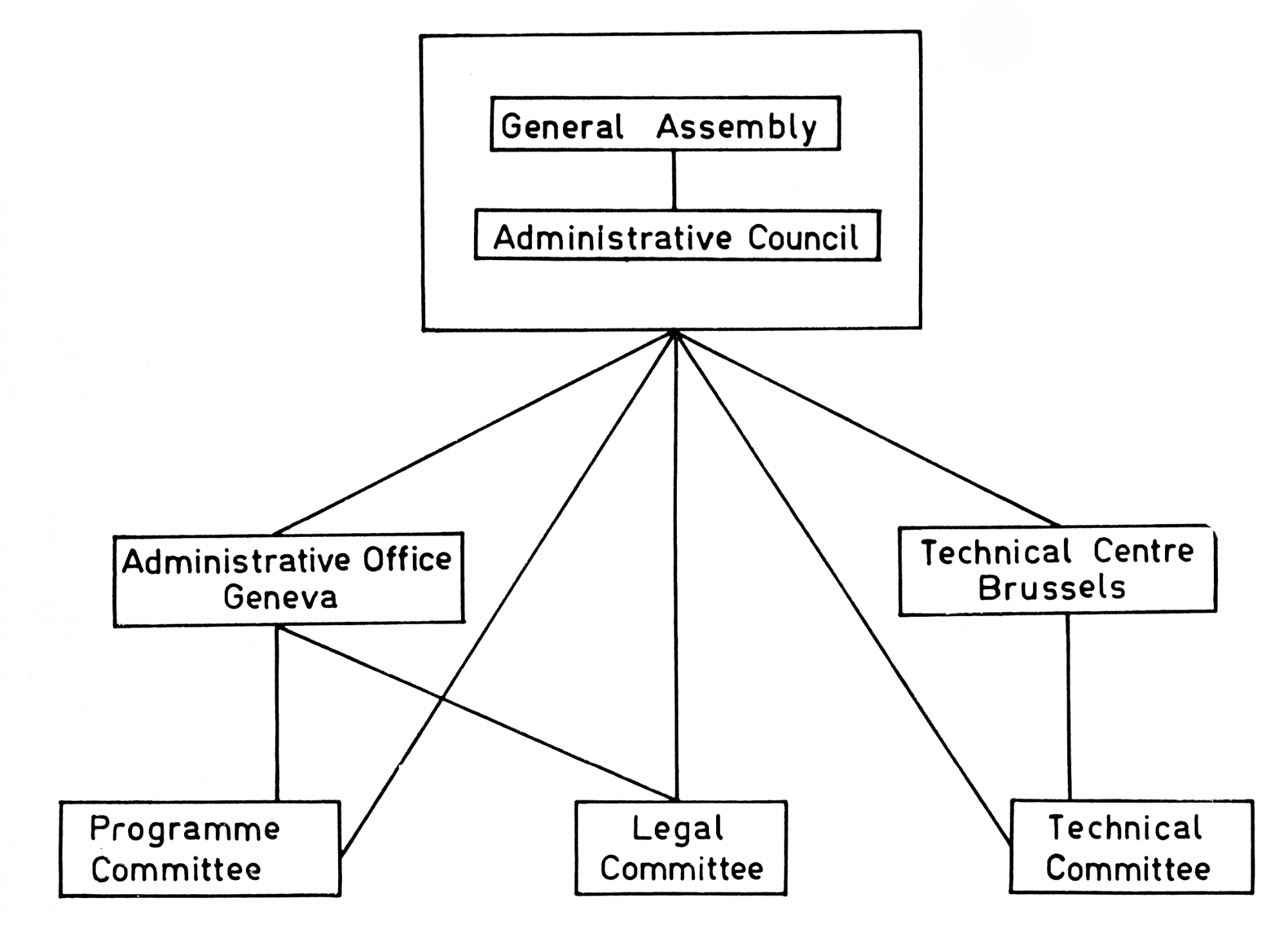

The table shown herewith represents in schematic form the organisation of the E.B.U.

E.B.U. organisational diagram.

The General Assembly is the supreme body of the Union. It is composed of all the Members of the E.B.U. and possesses full powers to achieve the social objectives of the Union.

The General Assembly meets once a year in ordinary session and can, if necessary, meet in extraordinary session. In particular, it elects the President and the two Vice-Presidents of the Union.

The President of the E.B.U. is Mr. O. Rydbeck, Director General of Sveriges Radio. He was preceded by Sir lan Jacob (B.B.C.) who is Honorary President of the Union. Mr. M. Rodino, Managing Director of the R.A.I. (Radiotelevisione Italiana), is Vice-President of the Union.

The General Assembly elects the members of the Administrative Council which represents the executive power of the Union.

The Administrative Council which at present consists of eleven administrators’ seats to which Active Members are elected, is charged with the execution of the decisions taken by the General Assembly. It meets at least twice a year and retains the rights and powers of the General Assembly between the ordinary meetings of that body. The Council examines and proposes notably to the General Assembly the establishment of committees charged with informing and advising it in the various fields of activity of the Union.

The E.B.U. General Assembly in session in Brussels, Belgium, 1962.

The Committees Three specialised Committees, the Programme, Technical and Legal Committees, that deal with the three extensive fields of activity of the Union, as well as a certain number of Study Groups, complete the organs of the E.B.U.

The Committees, through their specialists, play an important part within the Union. They are of a strictly consultative nature and report to the Council in all questions within their competence. They supervise the activities of the permanent establishments and study all the questions the solution of which might be of interest to Members.

Each Member of the Union has the right to be represented within each Committee which sets up its own internal regulations and elects a Bureau.

The Study Groups Each Committee may propose to the Council the setting up of Study Groups, in some cases called “Working Parties”, for the study of certain problems that require the collaboration of experts from the various sound and television broadcasting organisations. The competence of these working parties is restricted to the questions laid down in their terms of reference, and their activity ceases when those terms have been fulfilled. The role of the working parties is consultative, each working party reporting to the Committee of which it is part. The number of E.B.U. Working Parties varies during the course of the years and follows with flexibility the development of broadcasting. The description of the activities of the E.B.U. brings out the importance of the work accomplished by these small working parties whose meetings are one of the most lively forms of the E.B.U.’s activities.

The permanent establishments To handle its extremely diverse tasks and to coordinate the work it carries out with the participation of its Members, the E.B.U. has available two permanent establishments employing some eighty persons, including administrative staff, engineers and jurists, of different nationalities, who are normally recruited from the Members of the E.B.U.

The non-technical tasks are handled by the Administrative Office of the E.B.U., at the Registered Office of the Union at 1, rue de Varembé, Geneva. This is the permanent secretariat of the Union.

The Office includes the administrative, legal and programme departments of the Union and is accommodated in the very modern buildings of the International Centre on the Place des Nations. These departments deal notably with the non-technical aspects of international television programme exchanges.

At the meetings of the General Assembly and the meetings of the Administrative Council, the Director of the Administrative Office acts as Secretary General to these Assemblies.

The Director of the Administrative Office is Dr. Charles Gilliéron.

The Legal Adviser of the Union is Dr. Georges Straschnov.

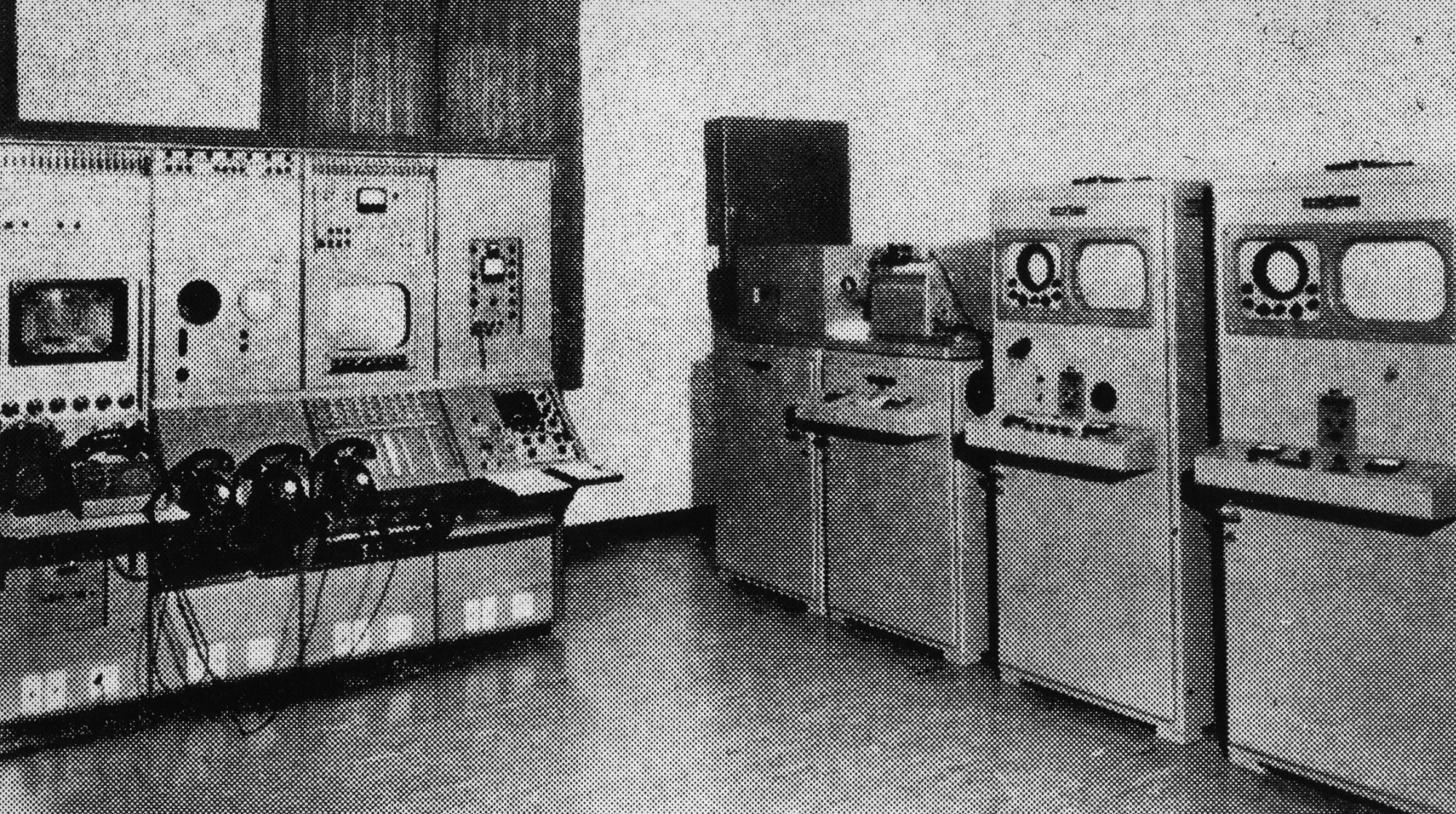

The Technical Centre of the E.B.U. is the permanent engineering organ of the Union.

Its central departments are accommodated in Brussels, at 32, avenue Albert Lancaster, Uccle, in a spacious building situated on the edge of the city.

The Technical Centre operates a Receiving and Measuring Station situated at Jurbise, to the south-west of Brussels.

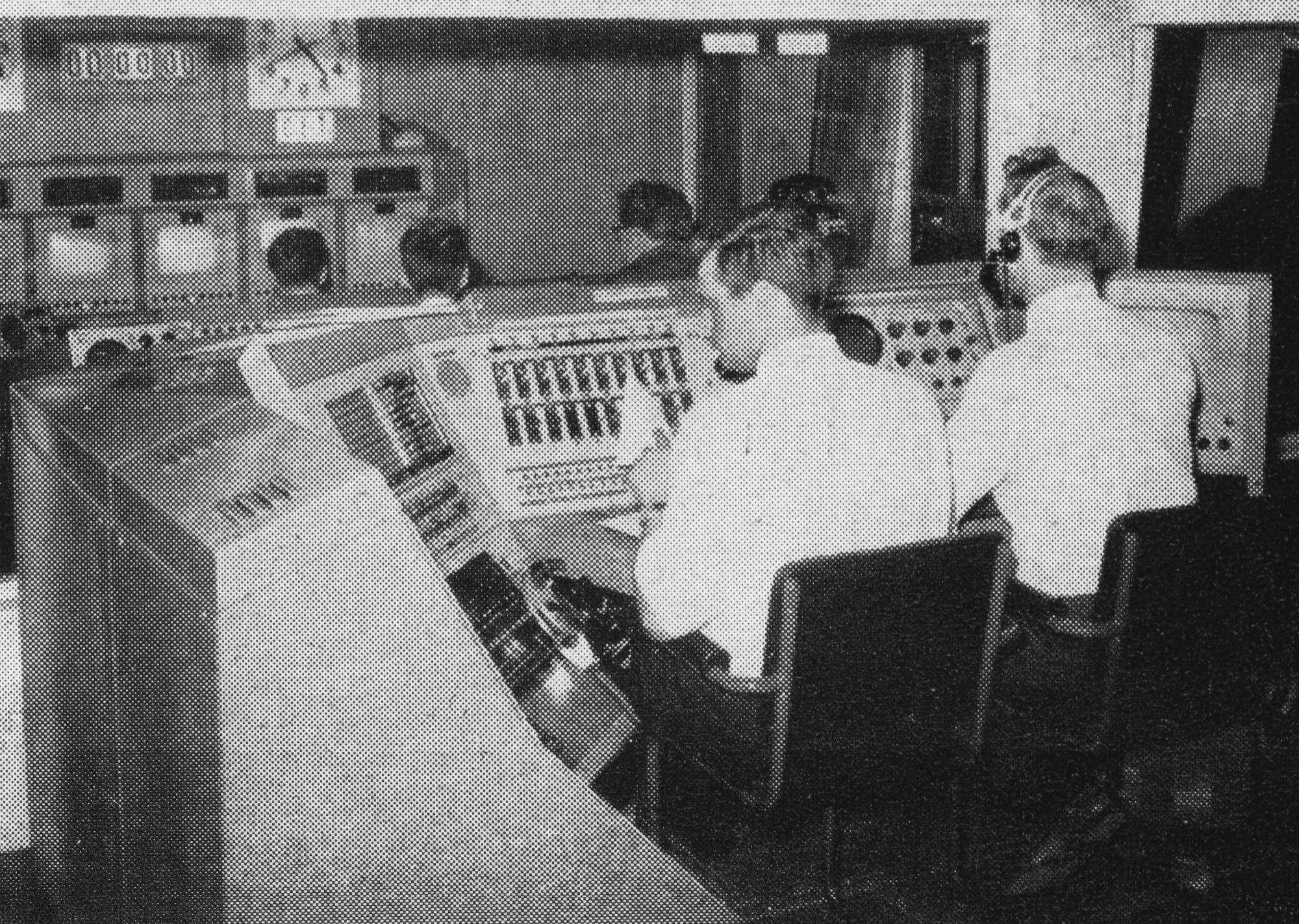

An International Coordination Centre for television programme exchanges, is also operated by the Technical Centre and is accommodated in the Palais de Justice in Brussels, which also houses the microwave link equipment of the R.T.B. (Radiodiffusion-Télévision Belge).

The Director of the Technical Centre is Mr. Georges Hansen.

The Chief Engineer is Mr. J. Treeby Dickinson.

The permanent establishments publish the E.B.U. Review, which is the Union’s main publication.

Financing the Union’s activities The expenses of the Union are covered by the Active and Associate Members, according to an annual budget voted by the General Assembly.

The Active Members of the E.B.U. pay a subscription for each financial year. The subscriptions of the Active Members, whose revenue is derived mainly from licence fees payable by users of receiving sets or from Government subsidies, are calculated in terms of the number of licences issued for payment on the 1st January preceding the beginning of the financial year in question. The subscriptions of the other Active Members are determined by the Administrative Council, having regard to the service operated and the particular position of each of these Members.

Associate Members pay no subscription, but contribute to the expenses of the Union, having regard to the services rendered by the latter and the financial resources of each of these Members. This share consists, on the one hand, of an annual contribution, the amount of which is fixed each year by the Administrative Council for each Member considered separately and, on the other hand, of a payment to compensate for any special work that might have been undertaken at their request by the E.B.U., the amount of this payment being fixed at the end of the financial year by the Administrative Council.

The building at Uccle, Brussels, occupied by the Technical Centre of the European Broadcasting Union.

This building, which was constructed in 1937 for the International Broadcasting Union (I.B.U), is situated in a residential district on the outskirts of Brussels. In 1961, an additional storey was added in order to cope with the expansion of the Technical Centre’s activities, in particular those relating to Eurovision. On the ground-floor, a conference room makes it possible for meetings of Working Parties and sub-groups to be held in the Centre.