Activities in the

Legal field

The raison d’etre and the justification for the E.B.U. is the existence of interests that are common to its Members, and it follows that common interests are best furthered by joint action. This concept of solidarity runs through all the legal activities of the E.B.U., whether undertaken by its Legal Committee or by its permanent staff. The explanation for this is obvious. Programme production and programme exchanges between organisations in different countries involve rights that are usually controlled on an international basis and can only be properly secured when this special situation is taken into account. For many decades copyright has been governed by multilateral Conventions, and the same is now true of the rights of performers and those of the phonographic industry. The music publishers have also banded together in an international association to confront the users of the scores they publish. Copyright works, the performances of musicians, singers and actors, commercial records and editions of operas, musical comedies and symphonic music are all the raw material of radio and television, without which these services could not exist. In its turn television has further complicated the lawyer s task. Films, works of visual art and “shows” of all kinds are consumed by television in vast quantities every day, whereas sound radio was either unable to give them at all or could only transmit the sound component. In addition to that, the development of certain new technical devices made it necessary to protect the broadcasts themselves against unauthorised appropriation by outsiders. The work of the legal departments of broadcasting organisations has therefore been growing steadily in recent years, and as these problems attain international dimensions they likewise increase the activities of the Legal Committee and its permanent secretariat, its study groups and its various negotiating delegations. The following brief account will undoubtedly bear out this statement.

INTERNATIONAL TREATIES

Members of E.B.U. belong to countries which are parties either to the Berne Convention or to the Universal Copyright Convention or to both, and accordingly it is of the utmost importance for them to be familiar with the exact operation of these international instruments and to keep a close eye on any possible revisions. The Universal Copyright Convention was only finalised in 1952 and has not been in effect long enough to warrant holding a revision conference. On the other hand the Berne Convention, the corner-stone of international copyright legislation in Europe, is already the subject of intensive work with a view to the Revision Conference to be held in Sweden in 1965. The E.B.U. Legal Committee is now studying the points on which a revision might be desirable and is preparing the basis for a common policy on the part of member organisations which will have to make representations to their governments in due course to ensure that the Convention is not revised in a manner prejudicial to their interests.

Towards the end of 1961 another Convention came into being. This Convention, which has direct and far-reaching implications for the broadcasting industry, is the instrument dealing with international protection for what are known as “neighbouring rights”, these being the rights of performers, record manufacturers and broadcasting organisations themselves. From its inception in 1950 the Legal Committee occupied itself with this problem, in the belief that a Convention on “neighbouring rights” would be concluded sooner or later, and played a very active and important part during the ten years that the Convention was on the stocks. The E.B.U. was present at every stage of the preliminary deliberations, was a member of all the Committees of Experts and was able to play a decisive role in the final drafting of the treaty through its contacts in the national delegations to the Diplomatic Conference. It may confidently be said that without this patient work over the years the Convention might have granted rights that would have had extremely serious repercussions on the operations of the broadcasting organisations.

At the specifically European level the Legal Committee plays a prominent part in the Intergovernmental Legal Committee on Broadcasting and Television functioning under the auspices of the Council of Europe. It is largely due to this fact that two European agreements have been concluded on the subject of television, both of which were modelled on the doctrine laid down in the E.B.U. Legal Committee. The first of these instruments, which six States have ratified to date, facilitates exchanges of television programmes by means of films and removes legal obstacles which, in the absence of such a treaty, might restrict films to exhibition in the country of origin alone. The second instrument to date ratified by four States and in the process of ratification by others, makes provision for domestic and international protection for television broadcasts against various forms of plagiarism, particularly the unauthorised reproduction of whole sequences or of still photographs off the screen, unauthorised wire diffusion and other forms of unlawful appropriation.

At the instance of the Legal Committee, the Council of Europe has at present under consideration a draft European agreement designed to put a stop to the activities of broadcasting stations operating contrary to international law on board vessels or aircraft in international waters or in international airspace.

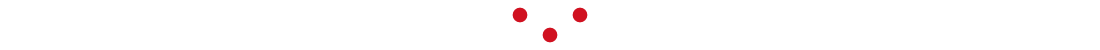

France signs the “European Agreement concerning Programme Exchanges by means of Television Films” at a meeting of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, 1958. In this view of the ceremony, Mr. Lenoble, President of the E.B.U. Legal Committee, is seen standing behind Mr. Couve de Murville, Minister of Foreign Affairs, France.

DOMESTIC LEGISLATION

At the national level the Legal Committee and its Secretary, the E.B.U. Legal Adviser, have frequently had occasion to consider the legislation in preparation in the various countries to which member organisations belong. Opinions have been expressed and advice given to ensure that the enactment in question, on such subjects as copyright, “neighbouring rights”, the organisation of broadcasting services, libel, etc., is as favourable as possible to the interests that the E.B.U. stands for. The Legal Adviser has had a hand in the framing of domestic Bills and continues to do so; this co-operation is beneficial to all the Members because the subjects in question — copyright and broadcasting — overstep national frontiers. This is also a form of technical assistance to under-developed countries, because this particular type of legal aid has been granted to several African countries at the request of the local broadcasting organisation belonging to the E.B.U.

The Legal Committee has also set up a special Working Party with the task of framing a model enactment for the new African countries, the purpose of which is to reconcile the legitimate interests of the various rightholders with the nation-wide needs of the broadcasting organisation.

Another Working Party is currently engaged in preparing a model domestic enactment on the protection of “neighbouring rights”, to which reference has been made above. The work of this Working Party will undoubtedly be of tangible benefit to many organisations.

INTERNATIONAL CONTRACTS

The proprietors of the rights which sound and television broadcasting require and use in their operations have joined forces in international associations, as mentioned above. It is therefore the obvious course for the E.B.U. to get into touch with these associations and endeavour in agreement with them to standardise the use of the rights they control. In this way several international standard contracts have been negotiated by the Legal Committee or by delegations it has appointed, and these contracts are used as the basis for domestic contracts and are applied at the present time by a large number of E.B.U. member organisations.

The earliest of these contracts was a contract signed with the organisation controlling a very wide international catalogue of musical works, with or without words, in respect of the right of reproduction. With such a tremendous growth in the magnetic recording of sounds and images, an international standard contract with a body authorised to license the recording of copyright works was an absolute necessity. The standard contract came into force in 1953 and, with successive revisions, still governs the recording of a world-wide repertoire of intellectual works in many countries where the E.B.U. has a Member.

Another standard contract was signed with the phonographic industry to determine in a uniform and equitable manner the general terms on which broadcasting organisations can use commercial records. The importance of this contract will increase as the international Convention on “neighbouring rights” might induce various countries to give the phonographic industry either a property right or a right to remuneration in respect of the use of records for broadcasting purposes.

Two other contracts with the music publishers which govern the rental of scores for recording and broadcasting purposes are widely applied at the domestic level. It is generally known that nowadays a music publisher does not print the works he controls or put them on public sale except in the form of piano arrangements or of excerpts, and that he has only a very small number of copies made of the scores required for full-dress performances. When a broadcasting organisation wishes to make a broadcast of such a work it has to hire these “materials” or scores. The Legal Committee had to work out very complicated clauses in the two contracts to cover all the possible situations that may arise in both sound radio and television. Discussions are now in progress with regard to the revision of these contracts.

Another international contract which the E.B.U. may sign once it has been finalised by the Legal Committee will dispose of certain problems raised by the international performers’ federations with regard to international exchanges of programmes in sound radio. These are mainly matters of a trade-union nature, and the agreement that may be signed will have all the features of an international collective agreement. It is hoped that it will have the effect of pacifying the unions’ apprehensions about what they consider to be the over-frequent use of recorded instead of live performances.

NATIONAL CONTRACTS

The standard contracts to which reference has been made above are used as pro-formas for the conclusion of national contracts. When the latter are being negotiated and when other contracts are being drawn up or when disputes arise at the national level between a member organisation and one of the bodies with which it has a contract, the E.B.U. Legal Department is often called in. Many national contracts have been negotiated or revised with the Department’s assistance. On the basis of the periodical surveys it makes, the Legal Department can inform Members at any time how much is paid in other countries for the acquisition of a particular type of right, and what contractual devices are used to effect a fair settlement of a given problem. Legal assistance in the contractual negotiations of member organisations is one of the E.B.U. Legal Adviser’s regular duties.

EUROVISION

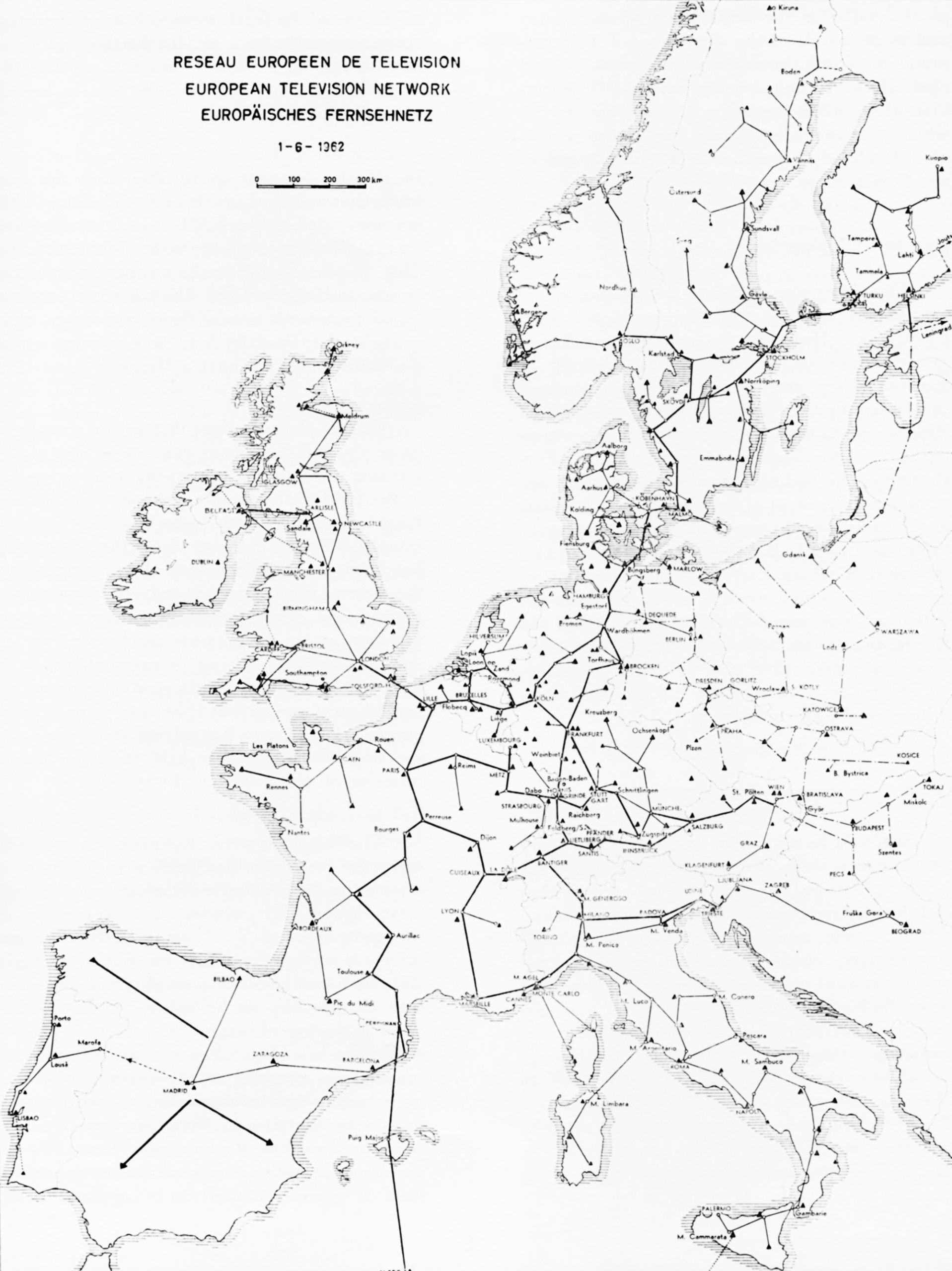

Eurovision has brought with it a host of questions that the Legal Committee has had to deal with urgently. It has been necessary, for instance, to overhaul the standard contracts which originally made no provision for this form of international co-operation, and to conclude others.

As far back as 1957 an international collective agreement was signed with the three international performers’ federations to determine, among other things, the size of the supplements which performers engaged at a fee would receive for a Eurovision broadcast, depending on the number of relaying organisations. This Convention, which is limited to the Members situated in the European Broadcasting Area, does not apply to intercontinental transmissions of professional performances via satellites.

It was found necessary to put the dealings with international newsfilm agencies on a firm contractual basis in order to settle the problems arising out of the contracts between these agencies and Eurovision. On the one hand, these agencies stand to gain by having their news items flashed over the Eurovision network, more speedily than by other means of transport, and on the other hand they would like to take from Eurovision certain news sequences that they have not obtained from their own correspondents. A standard contract and a set of rules laid down by the Legal Committee now govern these matters.

The increasing frequency with which sporting events are given on Eurovision has made it necessary to work out standard clauses for insertion in contracts for the purchase of the television rights in such events. The Legal Committee has had to consider several cases in this particular field, and it is the standing practice for the Legal Adviser of the E.B.U. to take part in negotiations relating to sporting events of international importance such as the Olympic Games or the various World Championships.

The desire of certain outside interests to forward closed-circuit transmissions over the Eurovision network has led the Legal Committee to make specific recommendations, and it has also had to consider the terms and conditions in contracts for the rental of circuits to be included in the future permanent network, in order that these contracts should correspond exactly to the requirements of the E.B.U. and of its Members.

No sooner have these problems been solved at the Eurovision level than they crop up again, with others, at the world-wide level on account of intercontinental transmissions via artificial earth satellites, now all accomplished fact. The Legal Committee will have to study the conditions to which such transmissions must conform in order to remain within the law not only in the originating country but also in the receiving country or countries. This is a problem of considerable magnitude, and so are the claims already being pressed by some of the contractual partners of the organisations likely to make such transmissions. In close cooperation with the legal departments of the member organisations in the American continent, the E.B.U. Legal Committee hopes to be able to resolve the problems that now lie before it.

COOPERATION BETWEEN THE COMMITTEE AND OTHER ORGANISATIONS

It would not have been possible to do everything that the Legal Committee has hitherto accomplished without frequent cooperation with other international bodies. Foremost among them are the intergovernmental agencies whose meetings are attended by the E.B.U., which is authorised to take part in the debates and expound its views. These are the various committees of the International Union for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, Unesco, the Council of Europe and the International Labour Organisation. At the non-governmental level the E.B.U., represented by the Legal Committee, is in regular touch with the international professional and trade organisations whose activities touch on those of the E.B.U. Sometimes standing joint committees are set up as a forum for periodic meetings, discussions and negotiations. Such committees have been set up with the International Confederation of Authors’ and Composers’ Societies (C.I.S.A.C.), the International Bureau of Mechanical Recording, the music publishers and the phonographic industry. Co-operation has also been established with the International Federation of Film Producers whose interests, on certain matters at least, run parallel with those of the E.B.U. The Legal Committee has always pursued a policy of being present at meetings, believing that the E.B.U. should be represented wherever the interests of its Members are at stake.

INTERNAL ORGANISATION OF THE COMMITTEE

The increasing number of participants at sessions of the Legal Committee is the best sign of the interest aroused by its activities. It also is significant that the Associate Members from other continents are attending sessions more and more frequently. The Bureau of the Legal Committee may be consulted by the permanent E.B.U. staff in urgent cases and it sometimes happens that the Committee entrusts it with certain tasks that have to be performed in the period between two sessions. The Chairman of the Committee is responsible for drawing up its agenda, for reporting on its sessions to the Administrative Council and the General Assembly, and for seeing to it that the decisions of these bodies are carried out.

The increasing range of its responsibilities may lead the Committee to decentralise more of its tasks, to set up more working parties than in the past and to give them more specialised terms of reference than it has hitherto done. This is the way in which it can probably best and most speedily live up to the expectations of the member organisations.