Members

E.B.U. MEMBERS (as at 30th June, 1962)

ACTIVE MEMBERS

| Austria | 1 | Oesterreichischer Rundfunk Ges.m.b.H. |

| Belgium | 2 | Radiodiffusion-Télévision Belge |

| Denmark | 3 | Danmarks Radio |

| Finland | 4 | Oy. Ylesradio Ab. |

| France | 5 | Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française |

| Germany (F.R.) | 6 | Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Oeffenlich-Rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (A.R.D.) |

| Greece | 7 | Hellenic National Broadcasting Institute |

| Iceland | 8 | Rikisutvarpid |

| Ireland | 9 | Radio Eireann - Telefis Eireann |

| Israel | 10 | Kol Yisrael - Israel Broadcasting Service |

| Italy | 11 | RAI - Radiotelevisione Italiana |

| Lebanon | 12 | Ministère de l'Orientation et de l'Information |

| Luxembourg | 13 | Compagnie Luxembourgeoise de Télédiffusion |

| Monaco | 14 | Radio Monte-Carlo |

| Netherlands | 15 | Nederlandse Radio-Unie |

| Norway | 16 | Norsk Rikskringkasting |

| Portugal | 17 | Emissora Nacional de Radiodifusao |

| 18 | RTP - Radiotelevisao Portuguesa | |

| Spain | 19 | Dirección General de Radiodifusión y Televisión |

| Sweden | 20 | Sveriges Radio |

| Switzerland | 21 | Société Suisse de Radiodiffusion et Télévision |

| Tunisia | 22 | Radiodiffusion-Télévision Tunisienne |

| Turkey | 23 | Basin-Yayin ve Turizm Genel Müdürlügü |

| United Kingdom | 24 | British Broadcasting Corporation |

| 25 | Independent Television Authority and Independent Television Companies Association Ltd. | |

| Vatican State | 26 | Radio Vaticana |

| Yugoslavia | 27 | Jugoslovenska Radiotelevizija |

ASSOCIATE MEMBERS

| Australia | 28 | Australian Broadcasting Commission |

| 29 | Federation of Australian Commerical Television Stations | |

| Burma | 30 | Burma Broadcasting Service |

| Canada | 31 | Canadian Broadcasting Corporation |

| Ceylon | 32 | Radio Ceylon |

| Congo | 33 | Radio Congo (Léopoldville) |

| Dahomey | 34 | Radiodiffusion du Dahomey |

| Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland | 35 | Federal Broadcasting Corporation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland |

| Ghana | 36 | Ghana Broadcasting Service |

| Haïti | 37 | Service des Télégraphes, Téléphones et Radiocommunications de la République d'Haïti |

| Japan | 38 | Nippon Hoso Kyokai |

| 39 | National Association of Commercial Broadcasters in Japan | |

| Morocco | 40 | Radiodiffusion Marocaine |

| New Zealand | 41 | New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation |

| Nigeria | 42 | Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation |

| Pakistan | 43 | Radio Pakistan |

| Republic of South Africa | 44 | South African Broadcasting Corporation |

| United States | 45 | American Broadcasting Company |

| 46 | Columbia Brodcasting System | |

| 47 | National Association of Educational Broadcasters | |

| 48 | National Broadcasting Company, Inc. | |

| 49 | National Educational Television & Radio Center and Broadcasting Foundation of America (International Division of NETRC) | |

| 50 | US Information Agency | |

| Upper Volta | 51 | Radiodiffusion de Haute-Volta |

Place des Nations

The headquarters of the European Broadcasting Union in Geneva, Switzerland, are situated in the Place des Nations at the nerve-centre of international life in Europe.

In the foreground of our photograph, the International Centre where the Administrative Office of the Union has its offices on the third floor. In the centre, the Palais des Nations, European Office of the United Nations; on the left, the new building of the International Telecommunications Union. Within a few minutes’ walking distance are the offices of the Bureau of the Berne Union and the International Labour Office. The European Broadcasting Union is in daily working contact with these major inter-governmental organisations.

Aims and Organisation

Its Aims and Organisation

Since the beginning of broadcasting, the broadcasting authorities have been aware of the value that lies in a close collaboration on the international plane. The imperative reasons acting in favour of such collaboration were:

- the very nature of radio waves, which ignore national frontiers;

- the similarity of the problems arising from the operation of broadcasting services in the different countries;

- the need to organise programme exchanges between broadcasting organisations;

- the complexity and interdependence of the problems posed from the technical, artistic and legal points of view, which called for a close collaboration between the engineers, programme staff and jurists of the different countries.

These reasons brought about the formation of a specialised international organisation whose activities include all aspects of broadcasting.

This organisation was, originally, the International Broadcasting Union (I.B.U.) which was formed at Geneva in 1925.

Since 1950, the European Broadcasting Union (E.B.U.) which succeeded the I.B.U., has fulfilled this task.

What is the E.B.U. ?

In law the European Broadcasting Union is a non-governmental international organisation whose object is to take care of the interests of organisations operating broadcasting services.

It is a private association, with no commercial aim, although it is an association of operating organisations.

The term “broadcasting service” should be taken in its most general sense, covering both sound and television broadcasting. It is, therefore, in this general sense that the term “broadcasting” should herein be understood, as it appears in the title of the Union, which includes both sound broadcasting and television organisations.

In French, the Union is called “Union Européenne de Radiodiffusion”, it being known in that language by the initials “U.E.R.” The two working languages of the Union are, in effect, French and English.

Professionally In the terms of its statutes, the aims of the European Broadcasting Union are:

- to support in every domain the interest of its affiliated broadcasting organisations and to establish relations with other broadcasting organisations;

- to promote all measures designed to assist the development of broadcasting in all its forms;

- to seek the solution, by means of international cooperation, of any differences that may arise;

- to use its best endeavours to ensure that all its Members respect the provisions of international agreements relating to all aspects of broadcasting

This enumeration of general principles guiding the E.B.U. in the orientation of its work permits judging the scope and diversity of its objectives, as will be shown in the description of its activities.

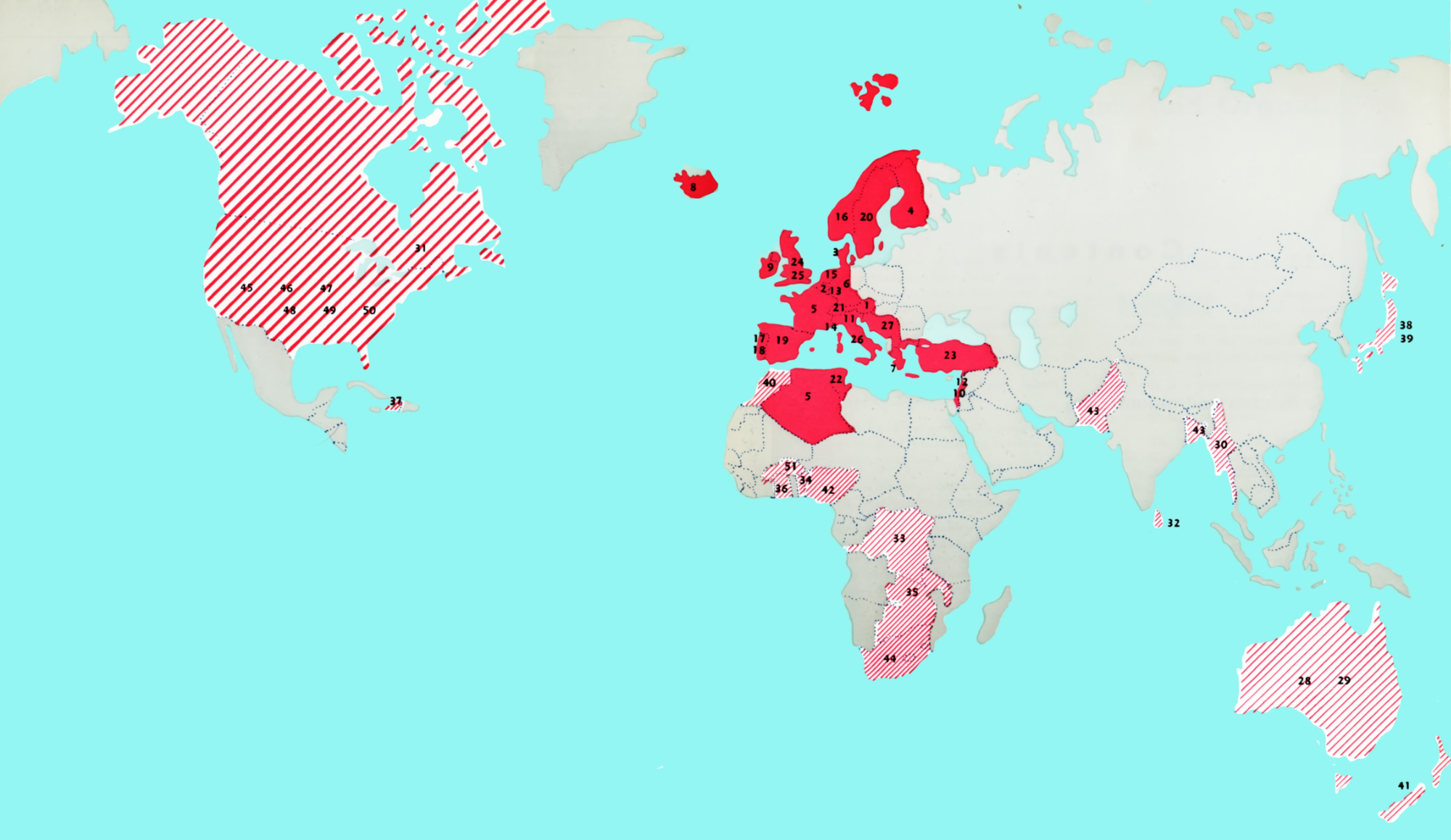

Geographically As its name indicates, the activity of the E.B.U. covers in the first place the countries of Europe, as well as the countries bordering on the Mediterranean, which, in the terms of the Conventions of the International Telecommunication Union (I.T.U.), are part of the “European Broadcasting Area”.

The activities of the E.B.U., however, extend outside Europe, a large number of extra-European broadcasting organisations having associated themselves with its work or achievements.

Thus the E.B.U. includes sound and television broadcasting organisations throughout the world, such organisations belonging to countries that are either members or associate members of the I.T.U.

- Only organisations within the “European Broadcasting Area” may belong to the E.B.U. as Active Members, that is to say, as members enjoying full rights.*

- Organisations in other parts of the world can belong to the E.B.U. only as Associate Members.

On 30th June, 1962, there were twenty-seven Active Members, in twenty-five countries:

Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany (Federal Republic), Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Jugoslavia, Lebanon, Luxembourg, Monaco, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey, United Kingdom, Vatican City.

On the same date, there were twenty-four Associate Members, all, except one, outside the European Broadcasting Area, in seventeen countries:

Australia, Burma, Canada, Ceylon, Congo (Leopoldville), Dahomey, Ghana, Haiti, Japan, Morocco, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, Rhodesia and Nyasaland, South Africa, United States of America, Upper Volta.

The map reproduced above gives an idea of the geographical distribution of the E.B.U.’s Members and Associate Members, the full alphabetical list of whom is shown in the table. It also shows that, thanks to the E.B.U., cooperation in the field of broadcasting has become a reality from one end of the world to the other.

* Nevertheless, by derogation of this principle, an organisation within the European Broadcasting Area, other than those of Continental Europe, Iceland, Ireland and the United Kingdom, may ask for admission as Associate Member instead of Active Member.

How does the E.B.U. work?

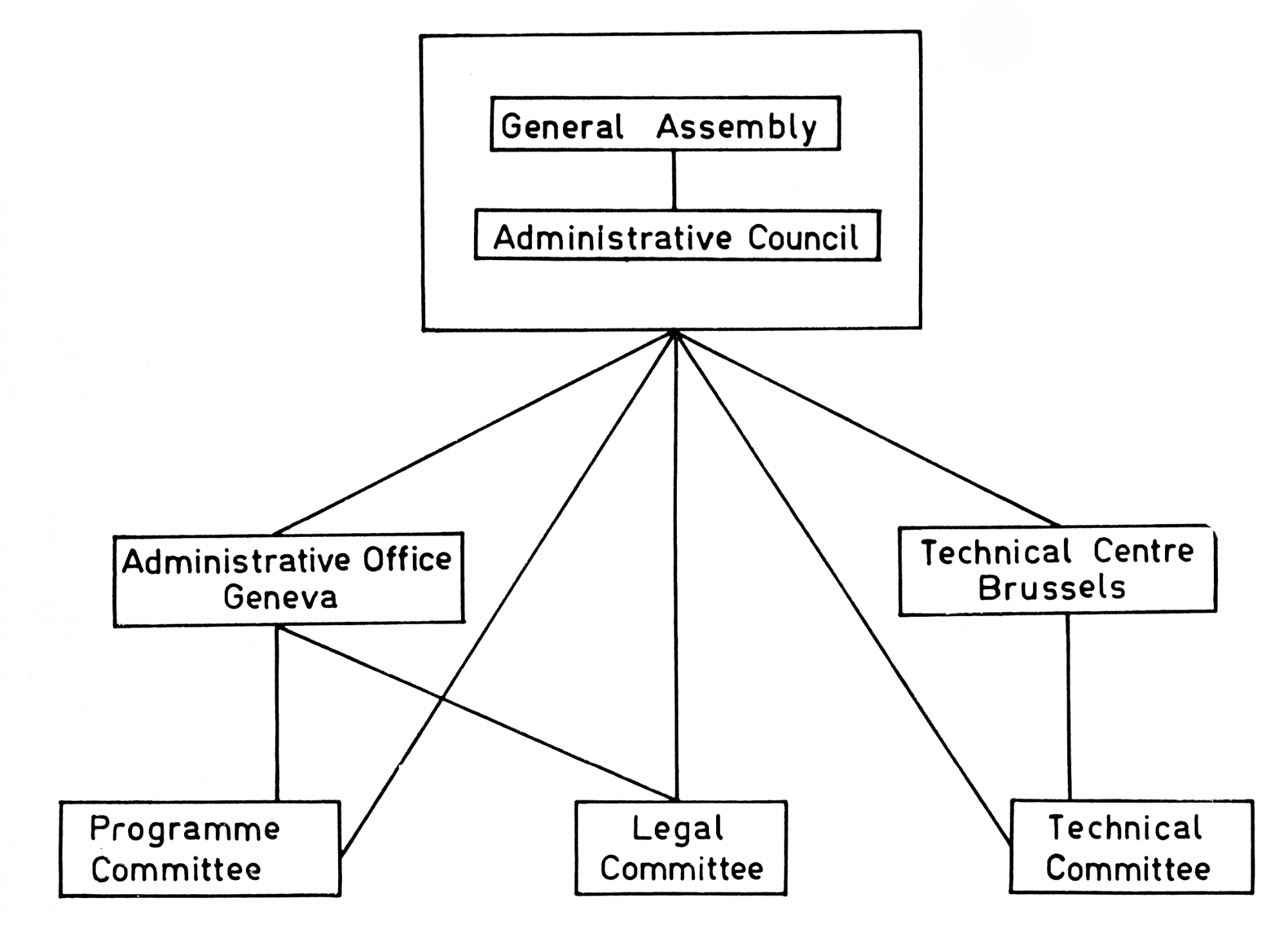

The general policy of the Union, the policy of decision in the orientation of its work, the determination of the programme of its activities, the admission or withdrawal of affiliation of E.B.U. Members, are dealt with by the General Assembly and the Administrative Council, whose activity concentrates on periodical meetings. The preparation of the decisions of these assemblies is the duty of the Union’s Committees, who play a consultative part, and of the permanent, executive, services.

The table shown herewith represents in schematic form the organisation of the E.B.U.

E.B.U. organisational diagram.

The General Assembly is the supreme body of the Union. It is composed of all the Members of the E.B.U. and possesses full powers to achieve the social objectives of the Union.

The General Assembly meets once a year in ordinary session and can, if necessary, meet in extraordinary session. In particular, it elects the President and the two Vice-Presidents of the Union.

The President of the E.B.U. is Mr. O. Rydbeck, Director General of Sveriges Radio. He was preceded by Sir lan Jacob (B.B.C.) who is Honorary President of the Union. Mr. M. Rodino, Managing Director of the R.A.I. (Radiotelevisione Italiana), is Vice-President of the Union.

The General Assembly elects the members of the Administrative Council which represents the executive power of the Union.

The Administrative Council which at present consists of eleven administrators’ seats to which Active Members are elected, is charged with the execution of the decisions taken by the General Assembly. It meets at least twice a year and retains the rights and powers of the General Assembly between the ordinary meetings of that body. The Council examines and proposes notably to the General Assembly the establishment of committees charged with informing and advising it in the various fields of activity of the Union.

The E.B.U. General Assembly in session in Brussels, Belgium, 1962.

The Committees Three specialised Committees, the Programme, Technical and Legal Committees, that deal with the three extensive fields of activity of the Union, as well as a certain number of Study Groups, complete the organs of the E.B.U.

The Committees, through their specialists, play an important part within the Union. They are of a strictly consultative nature and report to the Council in all questions within their competence. They supervise the activities of the permanent establishments and study all the questions the solution of which might be of interest to Members.

Each Member of the Union has the right to be represented within each Committee which sets up its own internal regulations and elects a Bureau.

The Study Groups Each Committee may propose to the Council the setting up of Study Groups, in some cases called “Working Parties”, for the study of certain problems that require the collaboration of experts from the various sound and television broadcasting organisations. The competence of these working parties is restricted to the questions laid down in their terms of reference, and their activity ceases when those terms have been fulfilled. The role of the working parties is consultative, each working party reporting to the Committee of which it is part. The number of E.B.U. Working Parties varies during the course of the years and follows with flexibility the development of broadcasting. The description of the activities of the E.B.U. brings out the importance of the work accomplished by these small working parties whose meetings are one of the most lively forms of the E.B.U.’s activities.

The permanent establishments To handle its extremely diverse tasks and to coordinate the work it carries out with the participation of its Members, the E.B.U. has available two permanent establishments employing some eighty persons, including administrative staff, engineers and jurists, of different nationalities, who are normally recruited from the Members of the E.B.U.

The non-technical tasks are handled by the Administrative Office of the E.B.U., at the Registered Office of the Union at 1, rue de Varembé, Geneva. This is the permanent secretariat of the Union.

The Office includes the administrative, legal and programme departments of the Union and is accommodated in the very modern buildings of the International Centre on the Place des Nations. These departments deal notably with the non-technical aspects of international television programme exchanges.

At the meetings of the General Assembly and the meetings of the Administrative Council, the Director of the Administrative Office acts as Secretary General to these Assemblies.

The Director of the Administrative Office is Dr. Charles Gilliéron.

The Legal Adviser of the Union is Dr. Georges Straschnov.

The Technical Centre of the E.B.U. is the permanent engineering organ of the Union.

Its central departments are accommodated in Brussels, at 32, avenue Albert Lancaster, Uccle, in a spacious building situated on the edge of the city.

The Technical Centre operates a Receiving and Measuring Station situated at Jurbise, to the south-west of Brussels.

An International Coordination Centre for television programme exchanges, is also operated by the Technical Centre and is accommodated in the Palais de Justice in Brussels, which also houses the microwave link equipment of the R.T.B. (Radiodiffusion-Télévision Belge).

The Director of the Technical Centre is Mr. Georges Hansen.

The Chief Engineer is Mr. J. Treeby Dickinson.

The permanent establishments publish the E.B.U. Review, which is the Union’s main publication.

Financing the Union’s activities The expenses of the Union are covered by the Active and Associate Members, according to an annual budget voted by the General Assembly.

The Active Members of the E.B.U. pay a subscription for each financial year. The subscriptions of the Active Members, whose revenue is derived mainly from licence fees payable by users of receiving sets or from Government subsidies, are calculated in terms of the number of licences issued for payment on the 1st January preceding the beginning of the financial year in question. The subscriptions of the other Active Members are determined by the Administrative Council, having regard to the service operated and the particular position of each of these Members.

Associate Members pay no subscription, but contribute to the expenses of the Union, having regard to the services rendered by the latter and the financial resources of each of these Members. This share consists, on the one hand, of an annual contribution, the amount of which is fixed each year by the Administrative Council for each Member considered separately and, on the other hand, of a payment to compensate for any special work that might have been undertaken at their request by the E.B.U., the amount of this payment being fixed at the end of the financial year by the Administrative Council.

The building at Uccle, Brussels, occupied by the Technical Centre of the European Broadcasting Union.

This building, which was constructed in 1937 for the International Broadcasting Union (I.B.U), is situated in a residential district on the outskirts of Brussels. In 1961, an additional storey was added in order to cope with the expansion of the Technical Centre’s activities, in particular those relating to Eurovision. On the ground-floor, a conference room makes it possible for meetings of Working Parties and sub-groups to be held in the Centre.

Its activities

Its Activities

What are the tasks of the European Broadcasting Union? What are the fields in which it is active? What are the services that it offers its Members?

As we have seen, its aims are laid down in its Statutes. These in fact enumerate the principles of action which have to be applied in a more precise form to the many and varied problems that arise in broadcasting.

Certain of these problems are of a continuing nature. There will always exist for the broadcasting organisations problems of copyright, of interference and of educational programmes. In this sense, it may be said that certain of the E.B.U.’s preoccupations in 1962 are the same as those that the I.B.U. was facing in 1936. However, progress constantly modifies the bases of the problems, and this necessitates reconsidering them and adapting the existing solutions to new situations.

There are also new problems consequent upon the development of the art, and these have to be solved with much science and at times with a certain empiricism.

Many problems, whether old or new, are best dealt with within the framework of a specialised international organisation. Such an organisation is the E.B.U. which, in Europe at present in full expansion, deals with all major problems concerning sound and television broadcasting.

Before enumerating the activities of the Union, it seems to us to he of some use to place them within their recent context, drawing special attention to some of the events that have marked the development of broadcasting in Europe and, indeed, in the world, during the course of recent years.

A few figures. . .

indicating recent developments in sound and television broadcasting in the European Broadcasting Area.

Transmitting stations

| Sound broadcasting on long and medium waves | ||

| Year | Number of stations in service | Total power |

| 1950 | 530 | 14,800 kW |

| 1952 | 675 | 17,800 |

| 1954 | 775 | 22,500 |

| 1962 | 1,260 | 36,700* |

| * Total power provided for in the Copenhagen Plan (1950): 20,000 kW | ||

| VHF sound broadcasting (Band II) | ||

| Year | Number of stations in service | Total power |

| 1952 | 100 | 1,000 kW (ERP) |

| 1955 | 210 | 3,900 |

| 1958 | 690 | 11,500 |

| 1960 | 1,300 | 14,000 |

| 1962 | 1,870 | 18,500* |

| * Total power provided for in the Stockholm Plan (1961): 72,800 kW | ||

| Television (Bands I and III) | ||

| Year | Number of stations in service | Total power |

| 1955 | 100 | 4,000 kW (ERP) |

| 1958 | 400 | 9,800 |

| 1960 | 920 | 15,400 |

| 1962 | 1,510 | 25,800* |

| * Total power provided for in the Stockholm Plan (1961): 57,400 kW | ||

Reception (E.B.U. Members only)

| Year (December) | Number of receiving licences for sound broadcasting | Number of receiving licences for television |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 45,372,298 | 423,550 |

| 1952 | 52,270,058 | 1,893,146 |

| 1954 | 59,215,291 | 4,503,041 |

| 1956 | 65,631,659 | 7,638,236 |

| 1958 | 69,105,512 | 14,318,054 |

| 1960 | 77,057,036 | 23,501,656 |

| 1962 (Jan) | 78,495,324 | 27,508,193 |

The European listener recalls with regret the happy period when all he had to do was to adjust the knobs of his receiver properly, in order to listen under relatively good conditions both on long and medium waves to the stations of his choice. Nowadays he needs to use much more patience and care, because of the overcrowding of that part of the radio spectrum.

In order to remedy this situation, recourse has had to be had to another waveband, namely that of the Very High Frequencies.

In addition to incontestable advantages from the technical point of view, from which the listeners have profited, this band has permitted the broadcasting organisations more flexibility in the planning of their programmes. On the artistic plane, it has introduced a new concept of listening (“high fidelity”) which may be deemed a step forward towards stereophony.

Concurrently with these developments, television has forged ahead. The work done by the research laboratories, by legal and programme experts, previously applied exclusively on the problems of sound broadcasting, gradually began to be applied to this technique, which was giving rise to new problems, especially those created by the development of television networks and links between transmitters and those concerning studio equipment. On the legal side, this new means of expression implied new rights that had to be defined and protected. On the cultural plane, it necessitates the exploitation of all the educational possibilities of television whose mission, it has been recognised, is not only merely to inform and to distract. School television has become for the broadcasting organisations a subject for study of the same importance as school broadcasting was for the sound-broadcasting authorities before the war. Moreover, the needs of each national network for varied programmes, including a wide coverage of life in other countries, required the organisation of programme exchanges between the various Members. This led to considering television on a continental scale and no longer on that of a single country or a single province. Eurovision, which was created some years ago, is giving a real picture of Europe.

Naturally, the attraction of television took away from sound broadcasting some of its listeners. It became necessary to seek out new objectives for sound broadcasting and to determine how to reorganise the programmes.

However, television was not the only important problem that confronted the European broadcasting organisations after the war. The modification of certain operating techniques (that of sound recording, for instance) necessitated the adaptation or replacement of the equipment and necessitated changes in the working methods.

From a more general point of view, the development of automatic equipment made it possible to economise in staff and modified the economic and social aspects of one part of sound-broadcasting operation. The introduction of new components in the equipment (such as the transistor and the vidicon) brought about reductions in weight and in the bulk of the apparatus and opened the road to new possibilities for programme producers.

Finally, certain new techniques made their appearance: stereophony, colour television, the use of artificial earth-satellites, attracting the interest of specialists and becoming the object of study and research on an international plane.

It should be stressed that these new facilities did not get rid of the problems confronting broadcasting in a more current form. The solution of these more ordinary problems is in fact of great interest to many of the recently-created countries which require help in the organisation of their broadcasting networks and equipment. In this field, too, a coordination of efforts on an international level has proved to be necessary.

These, then, are the more important circumstances that are dictating the main direction of the E.B.U’s activities. These are the activities that we shall now describe, beginning with the activities of the Union’s three Specialised Committees, namely, the Programme Committee, the Technical Committee and the Legal Committee.

Activities in the Programme field

Activities in the

Programme field

Work of the Programme Committee

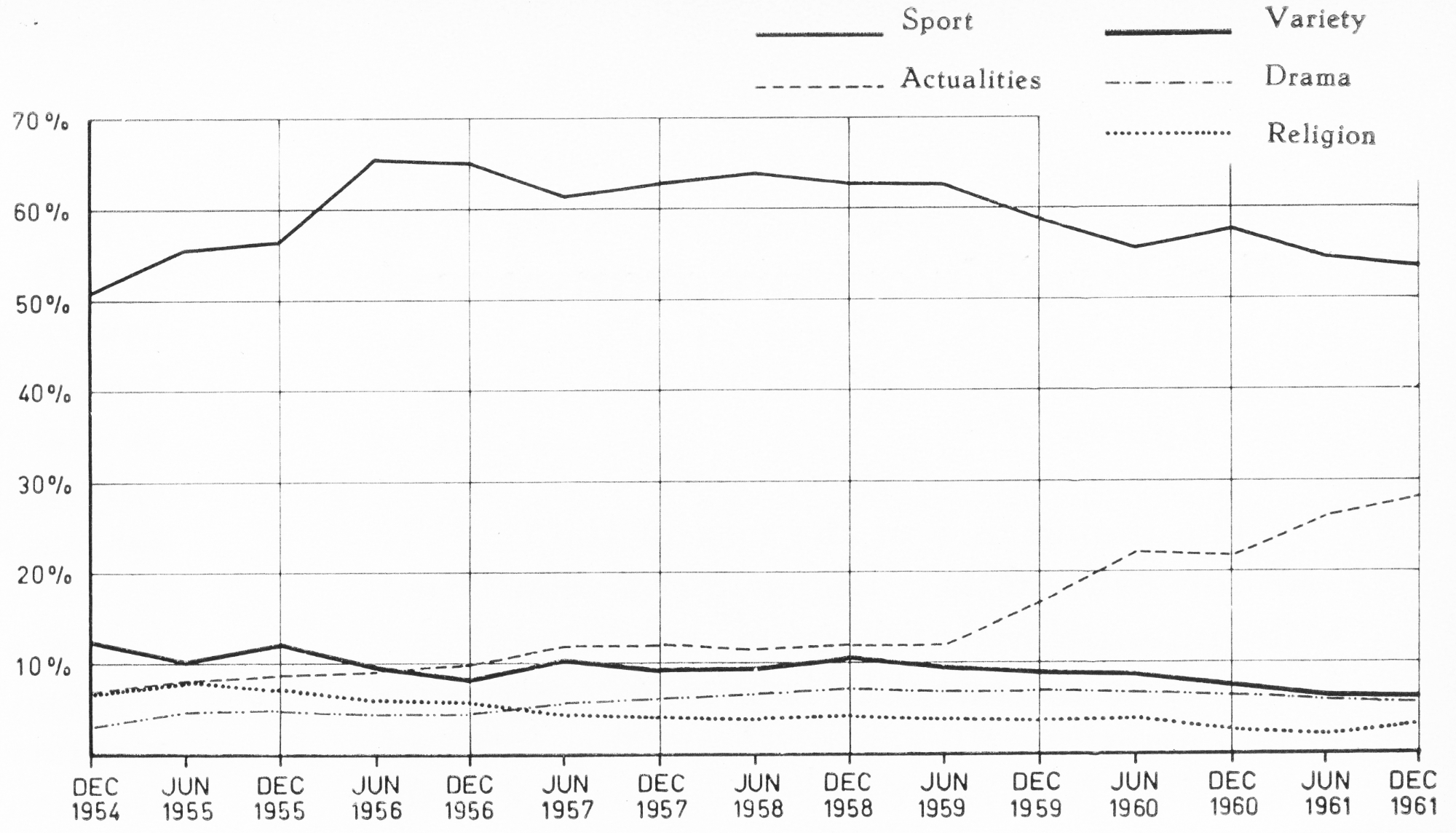

When the E.B.U. was founded at Torquay on 12th February 1950, the Legal and Technical Committees were set up immediately by decision of the General Assembly. Some three years later, on 10th November 1953 to be precise, the Programme Committee was created at the proposal of the Administrative Council. This Committee whose task has grown increasingly important, especially since the development of television, meets twice a year, in the spring and autumn, and has as members the television programme directors of the Union’s member organisations or their delegates. This permanent body’s province is the study of all the general aspects of the field which has been assigned to it and its terms of reference are, more particularly, to deal with the problems raised by international exchanges of programmes and first and foremost those relating to television. Under this heading may be included direct exchanges and exchanges on film, news exchanges, and special programmes.

The main work of the Programme Committee consists in preparing international programmes, studying the problems posed by staff training and making provision for international exchanges in many fields, but the Committee does not for that reason ignore the problems arising from the repercussions of such work on the legal and technical spheres.

That is why the Programme Committee works, whenever necessary, in close cooperation with the Technical and Legal Committees.

Activities of the Study Groups

Each Committee is entitled to set up, where necessary, study groups composed of experts in a particular field. The Chairman of a study group, whose competence extends only to the question which has been referred to it for study, is always a director who is a member of the Committee, so that liaison with the Committee can be maintained and the work conducted in a realistic, useful and efficient manner. The secretariat of these bodies is provided, in the interests of coordination, by the Administrative Office which plays an active and practical part in the work of the Programme Committee’s study groups.

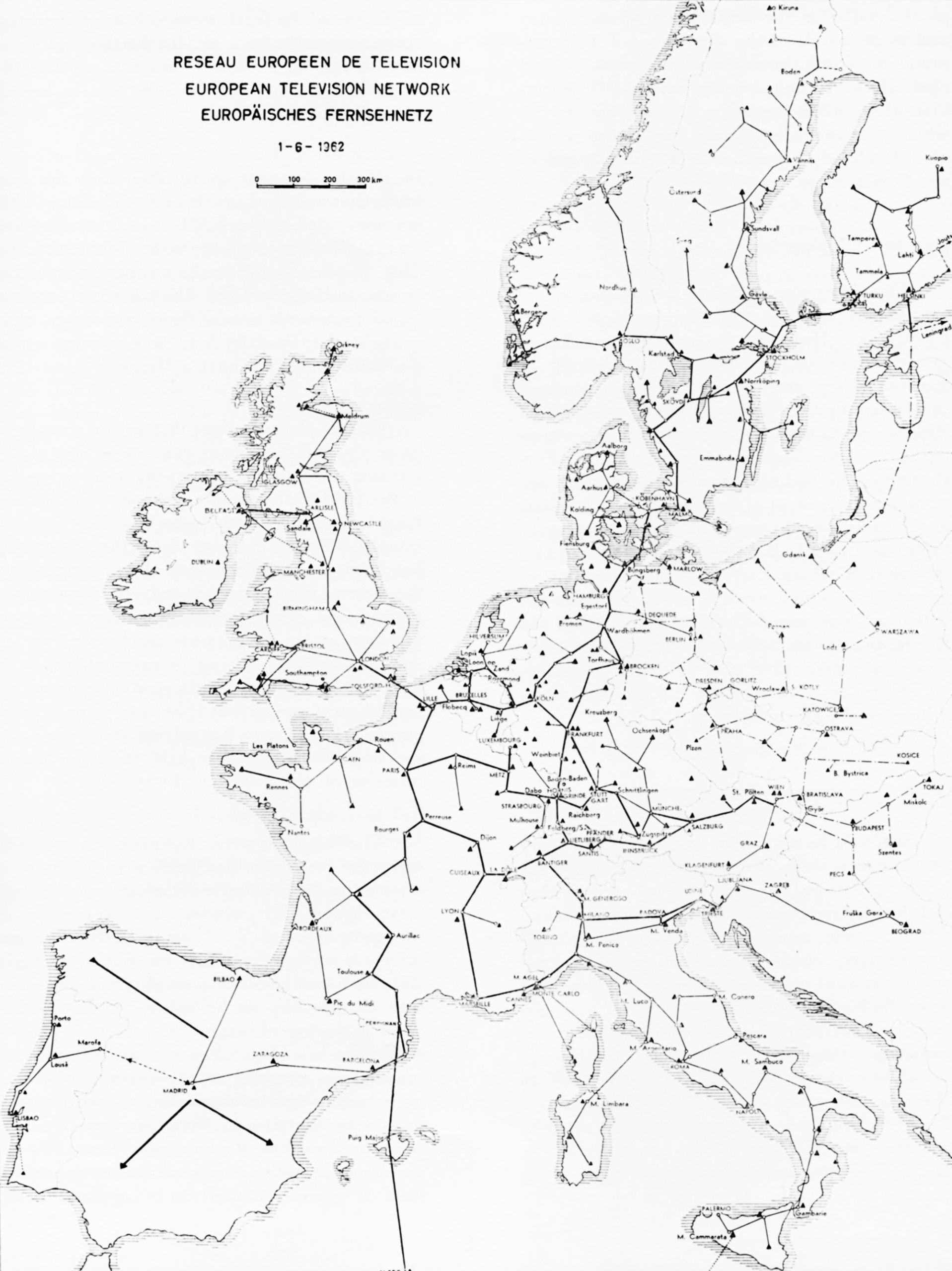

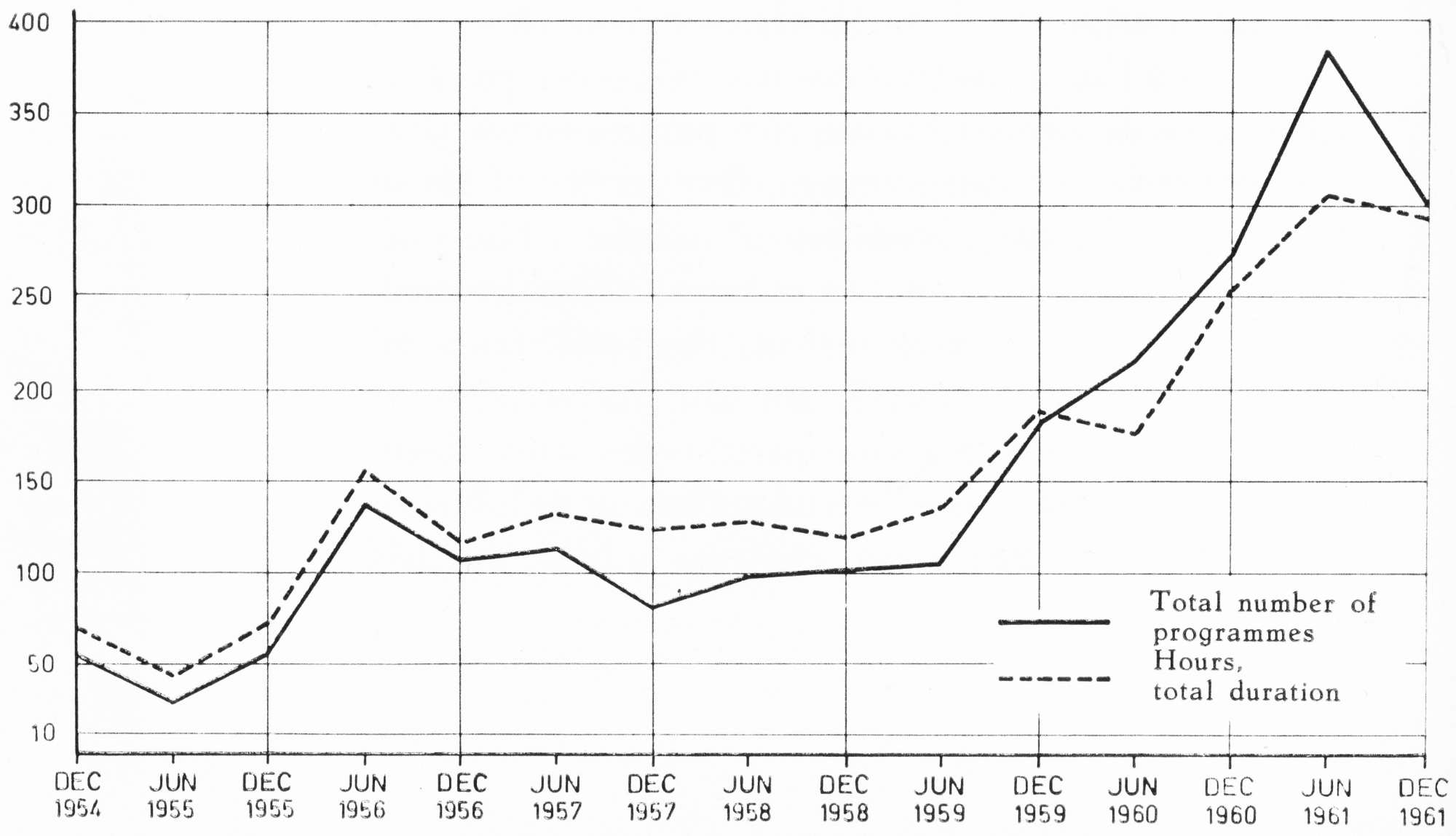

The international television relays over the Eurovision Network, the Daily News Exchange Scheme, the organisation of special international programmes, such as the agricultural and youth magazines, and television for schools, are among the principal activities which the E.B.U. Programme Committee has entrusted to its Study Groups and which we shall describe briefly.

Planning Group

The Planning Group is mainly responsible for the organisation and coordination of the majority of programme exchanges of important topical events, known as Eurovision. This function is specified in the description of Eurovision operations later.

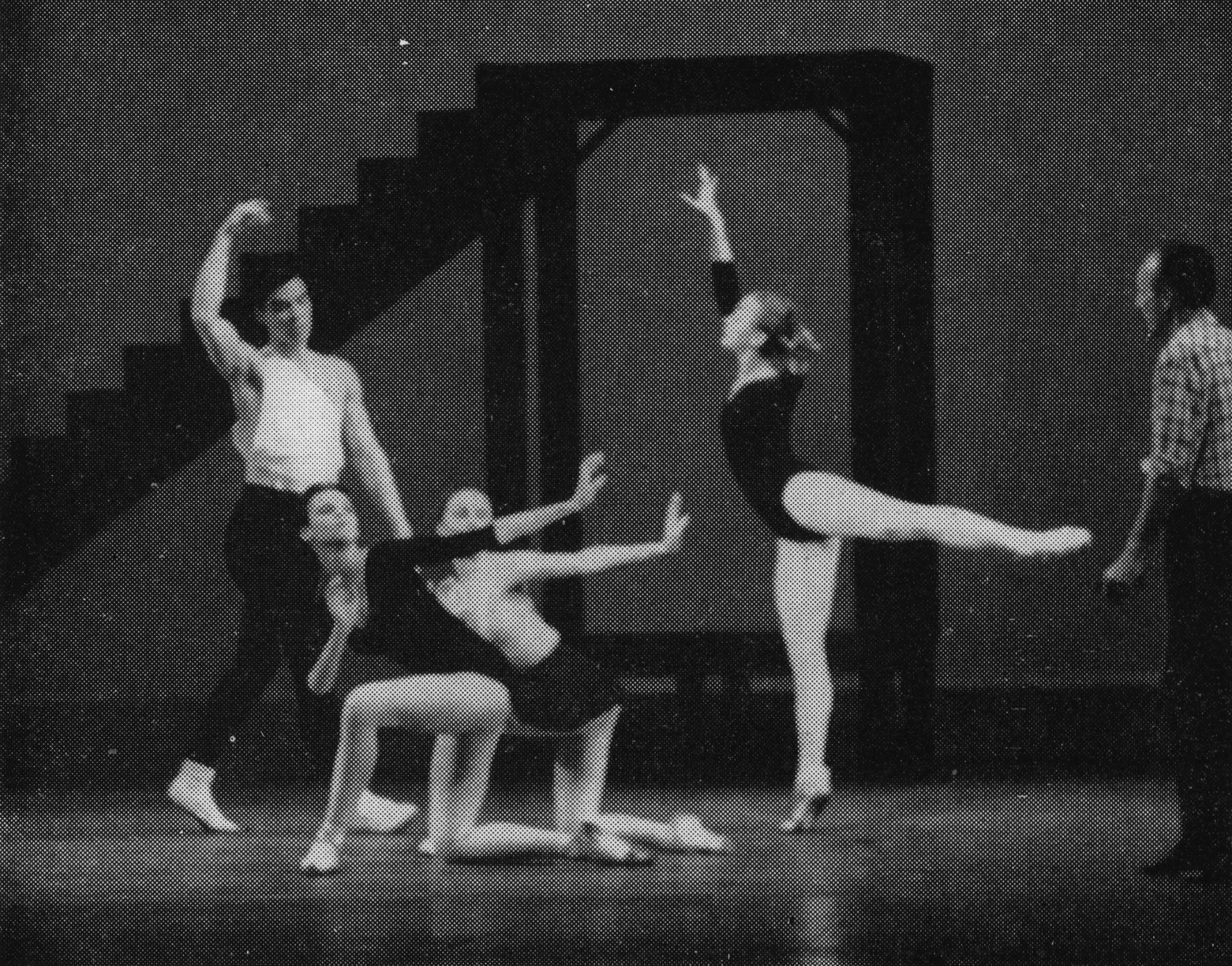

Among the important tasks that fall to this Group are the Grand Prix of the Eurovision Song Contest, the implementation of the project entitled “The Largest Theatre in the World” and relays of major sporting events such as the world football, ice hockey, athletics and gymnastics championships, or the summer and winter Olympic Games, among other things.

The latest statistics issued at the end of 1961 indicate that 2275 Eurovision programmes for a total of 2366 hours had given rise to 12,733 relays.

News Exchanges

The News Exchange Study Group deals with the daily exchange of news which is distributed in closed circuit over the Eurovision Network. This news is recorded by all the participating services for use in their television newsreels the same evening. In the last few months these exchanges have expanded considerably and have helped to speed up the supply of information and make a valuable contribution to television newsreels.

Within the framework of the programme exchanges, the E.B.U. decided to organise two series of large-scale special international magazine programmes, which the diversity of the material contributed by the participants has rendered extremely interesting. Two of the Study Groups of the Programme Committee have been responsible for such series: the Agricultural Programme Study Group and the Children’s Programme Study Group.

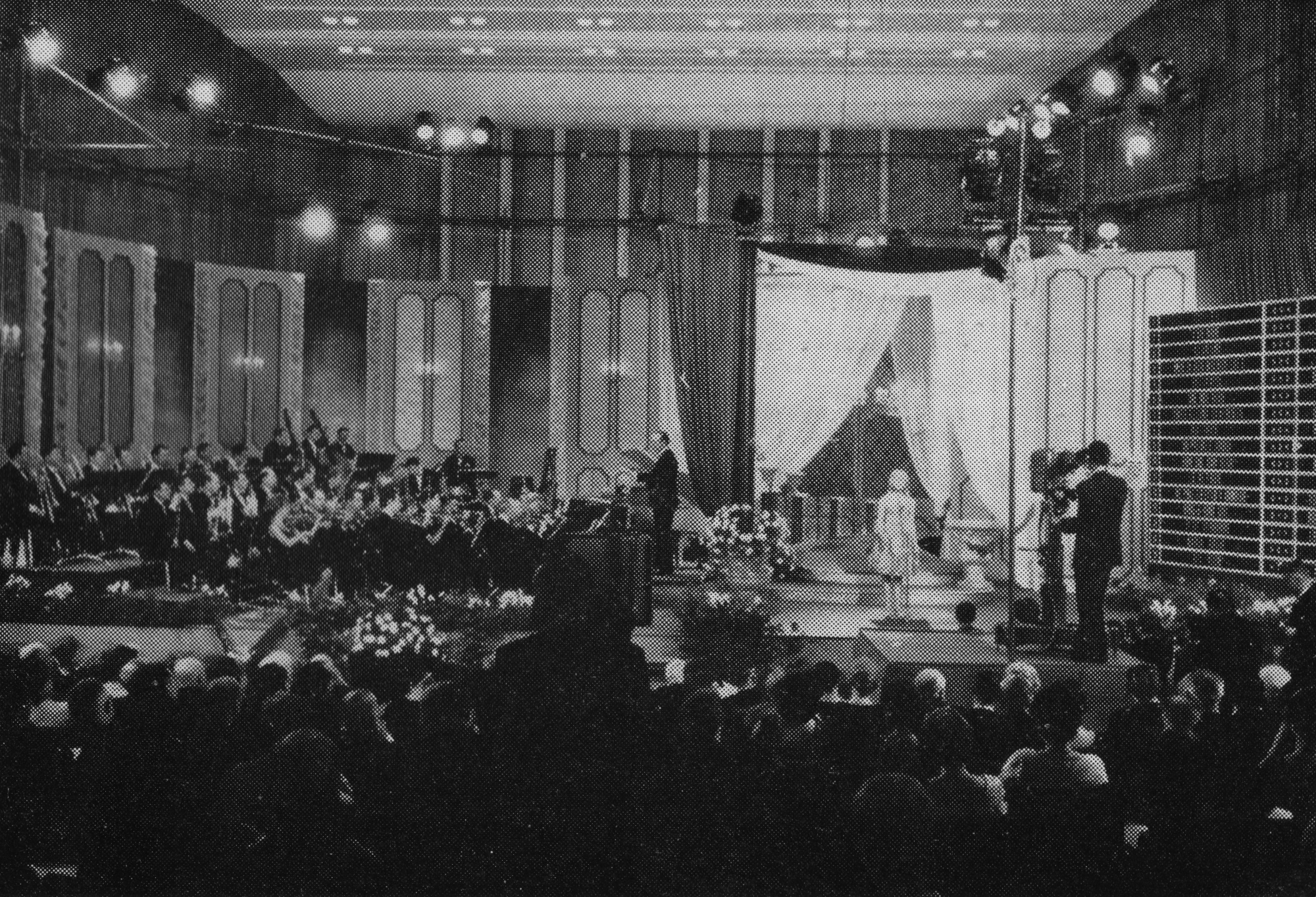

View of the main hall of the Palazzo dei Congressi, Rome, where the International Conference of Radio and Television Organisations on School Broadcasting was held in December 1961. This conference was initiated by the E.B.U. and organised by the Radiotelevisione Italiana.

Agricultural Programme

The production of an international agricultural magazine programme comes within the province of the Agricultural Programme Study Group. Each organisation supplies an average of six subjects per year for agricultural films, and uses between thirty and fifty subjects of foreign origin. The Group is also studying a joint production on “European cattle”, and it is trying to devise a system of mutual information relating to available material, plans for outside broadcasts etc.

Children's Programmes

The Children’s Programme Study Group is responsible for producing another international magazine, for children in this case. The Children’s International Magazine has been in existence for several years and the experts in this Group endeavour in the course of their meetings to find ways of developing and improving it. Other types of exchanges are also given careful study; these include exchanges of documentary films and film series, or live and deferred transmissions.

Educational Television

Several questions are studied by the Educational Television Study Group whose main objectives it would be interesting to list: to provide teaching circles with fuller information on the possibilities of school television; to set up and circulate a card index keeping member organisations informed of material available for exchange; to study coproduction projects; to promote study tours for specialised production staff, particularly those responsible for animation and visualisation; to organise in-service training courses for producers of school television; and finally to produce the first international series of school programmes, on economic geography.

• •

Apart from its activities directly related to the programme material, the E.B.U. has concerned itself particularly with the problem of the training of programme staff and has organised many schemes having that purpose in view. Moreover, the E.B.U. has collaborated directly in the work of the more important international bodies and participates in the organisation of several international artistic festivals.

Staff training problems

A product of the Educational Television Study Group was the training course, entitled “From Idea to Image”, intended for directors and producers with a certain general experience of television, which was held in Basle from 7th to 14th February 1962. This school-television course, organised by the 🇨🇭 S.S.R., met with great success. There were more than 31 participants and 19 active and associate Members of the E.B.U. were represented. Fifteen teachers contributed to a review of the many educational problems connected with school television. Thirty-three programmes were viewed and discussed.

Mention should also be made in this field of the course organised by the 🇬🇧 B.B.C. for television designers. This took the form of a conference on television scenic design held in London from 7th to 15th May 1962 and was acknowledged to be a great success.

The same can be said of the 3rd international course for television producers on “the broadcast drama” which was organised by the 🇫🇷 R.T.F. from 28th May to 16th June 1962 in Paris and whose lectures were of tremendous interest to the many participants.

Nor should we forget the very important part played in the international field by the International Conference of Radio and Television Organisations on School Broadcasting organised by the 🇮🇹 R.A.I. in Rome from 3rd to 9th December 1961 and sponsored by the E.B.U.. Delegates from 64 countries were thus given the opportunity to take stock of past experience and consider future plans in the field of school broadcasting.

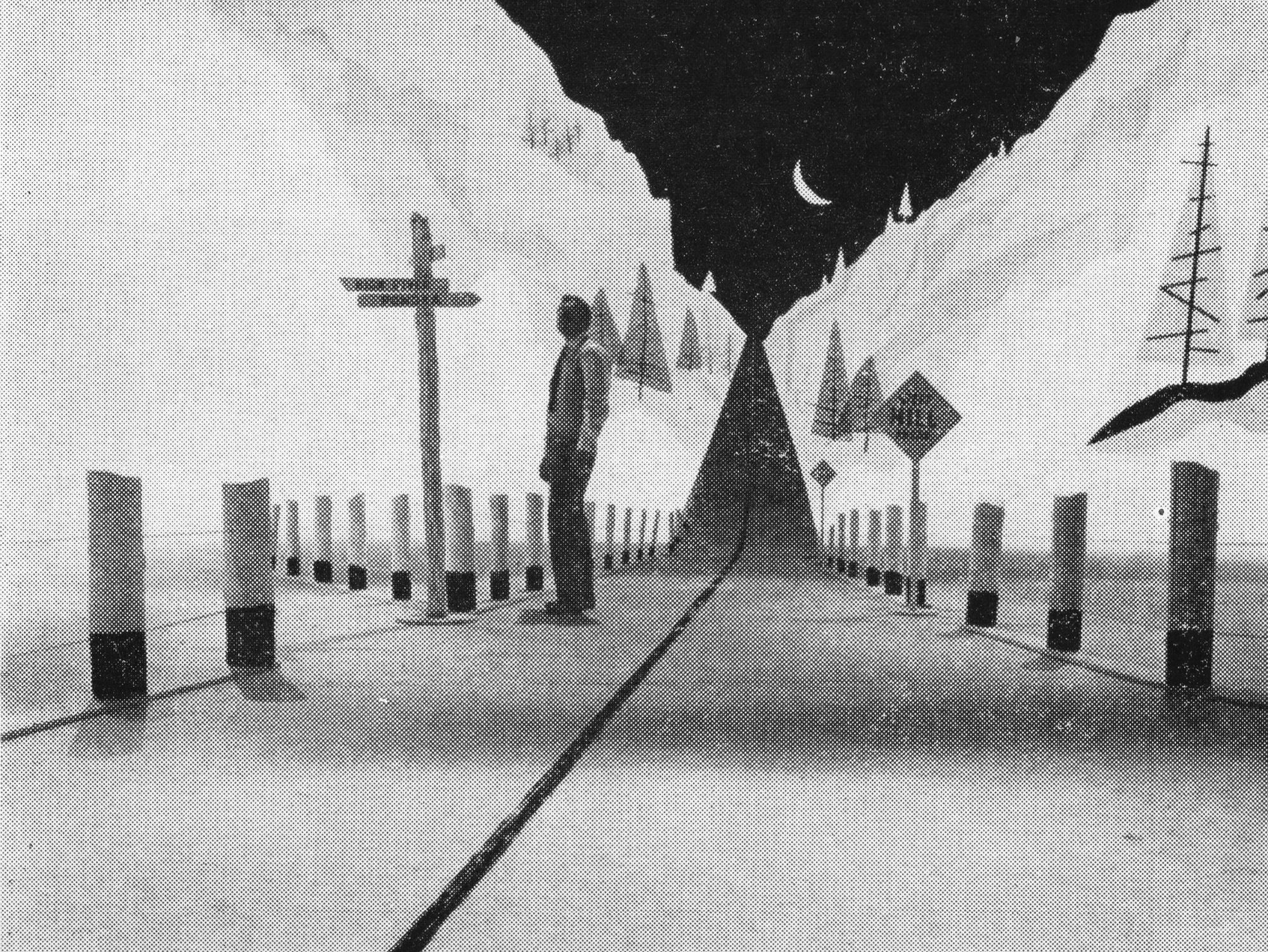

▼ Several issues of the E.B.U. Review – Part B have been devoted to television scenic design. These two examples were among the many described.

Set for a television variety programme entitled Music ’60, presented by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

Co-operation with other International Organisations

Another of the E.B.U.’s activities at the international level is its cooperation with a large number of important international organisations including the 🇺🇳 United Nations, Unesco, the World Health Organisation, the International Labour Organisation, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the International Film and Television Council and the International Union for Child Welfare. In this field, the E.B.U. originates and encourages a wide variety of activities which have a direct bearing on the international scene, often in connection with the anniversaries of these institutions.

The same spirit of cooperation prompted the E.B.U. to attend the important meeting on educational broadcasting in tropical Africa organised by Unesco in Moshi (Tanganyika) in September 1961. The Union was also represented at the Unesco meeting in Paris in January and February 1962 on the development of information media in Africa.

Rural broadcast training course for Asians enabling students to study the work of the Rural Department of the Australian Broadcasting Commission. This is one example of the help that E.B.U. Members are giving to developing nations.

International Festivals

In the field of major international meetings, the E.B.U. has taken important measures to avoid a chaotic proliferation of international competitions and to prevent these competitions and festivals from overlapping and duplicating each other. This has allowed the Union to adopt a favourable position with regard to competitions and festivals whose regulations have been submitted to it in good time and have received its approval.

The names and main characteristics of these international radio and television competitions are as follows:

The Eurovision Grand Prix of Television Films, Cannes, reserved to films specially produced and devised for television by independent producers; the Golden Rose of Montreux Contest, for television variety broadcasts; the International Television Festival, Monte Carlo; the Salzburg Opera Prize.

Mention should also be made of the traditional Prix Italia, awarded to the best dramatic, musical and documentary works, which is organised independently and is financed by broadcasting organisations that are for the most part members of the E.B.U.

Special course in broadcasting for visitors from overseas, organised by the B.B.C. in the spring of 1957. Visitors from Cyprus, Hong-Kong, Uganda, Aden and Sierra Leone are seen here rehearsing for a feature programme exercise.

Activities in the Technical field

Activities in the

Technical field

Sound and television broadcasting are, then, in a sense newcomers among the mass media and their technical development has not yet reached finality. As we have seen, VHF/FM services, colour television and stereophonic broadcasting have been introduced during the past ten years, but there are other technical innovations, the importance of which is obvious only to the specialist. Let us mention as an example those new terms that have enriched (or perhaps we should say, impoverished) our language during past years: transistor, klystron, vidicon and so on. These inventions, which fill the engineer with enthusiasm may well offer interesting possibilities for improving broadcasting or for extending the field of its action, but they cannot be introduced before they have been studied with a view to their routine exploitation and the economic repercussions that they may have.

For these reasons, most of the broadcasting organisations possess research laboratories of varying size that work in close liaison with their operational departments. Some of their research work — that concerning the propagation of radio waves, for instance — by its very nature extends beyond the national frontiers. Other work can advantageously be shared among several countries. Some again requires a standardisation, on the international plane, of methods and equipment.

This is where the E.B.U. comes in, its role being to keep its Members informed concerning the progress of such research work and to coordinate such as is of most interest to them.

In fixing its study and working programmes, the Union always takes into consideration the activities of other international organisations already handling similar questions. These are notably the International Telecommunication Union (I.T.U.) which is a governmental organisation of world-wide competence, its consultative committees (C.C.I.R. and C.C.I.T.T.),, and its International Frequency Registration Board (I.F.R.B.), the Conference of European Postal and Telecommunication Administrations (C.E.P.T.), which is a governmental organisation of European competence, the International Standards Organisation (I.S.O.), the International Electrotechnical Commission (I.E.C.) and its International Special Committee on Radio Interference (C.I.S.P.R.), which are industrial organisations, and the like. The E.B.U. as often as possible organises its own activities having regard to the working programmes of these organisations and in liaison with them, so as to avoid any duplication of work. Moreover, the E.B.U. brings to their attention new questions for which it would be interesting to find a solution on the international plane, either at governmental level or within the framework of industry.

The coordination of the technical work undertaken by the Members of the E.B.U. is ensured, on the one hand, by the Technical Committee — in particular by its Working Parties (of which there are eight at present) and, on the other hand, by the Technical Centre of the E.B.U. in Brussels, which acts as secretariat to these organs and which often takes an active part in the studies themselves. The Technical Centre also accepts other tasks that present an interest for all E.B.U. Members: the monitoring of transmissions done by its Receiving and Measuring Station at Jurbise near Mons, which we shall discuss later, and the technical coordination of Eurovision by its International Technical Coordination Centre, whose functions are explained in the Chapter on “Eurovision”.

Let us now look at some of the matters dealt with by the E.B.U.

WAVE PROPAGATION

It is most important for broadcasting organisations to know how the waves that carry their programmes are propagated. In effect, propagation, apart from its useful effects, may prove to be harmful to the extent that the waves cannot be strictly contained within the desired service area of the transmitters, and consequently they cause disturbances, either by interfering with the signal of another transmitter, or by causing degradation of the wanted signal through the behaviour of the propagation.

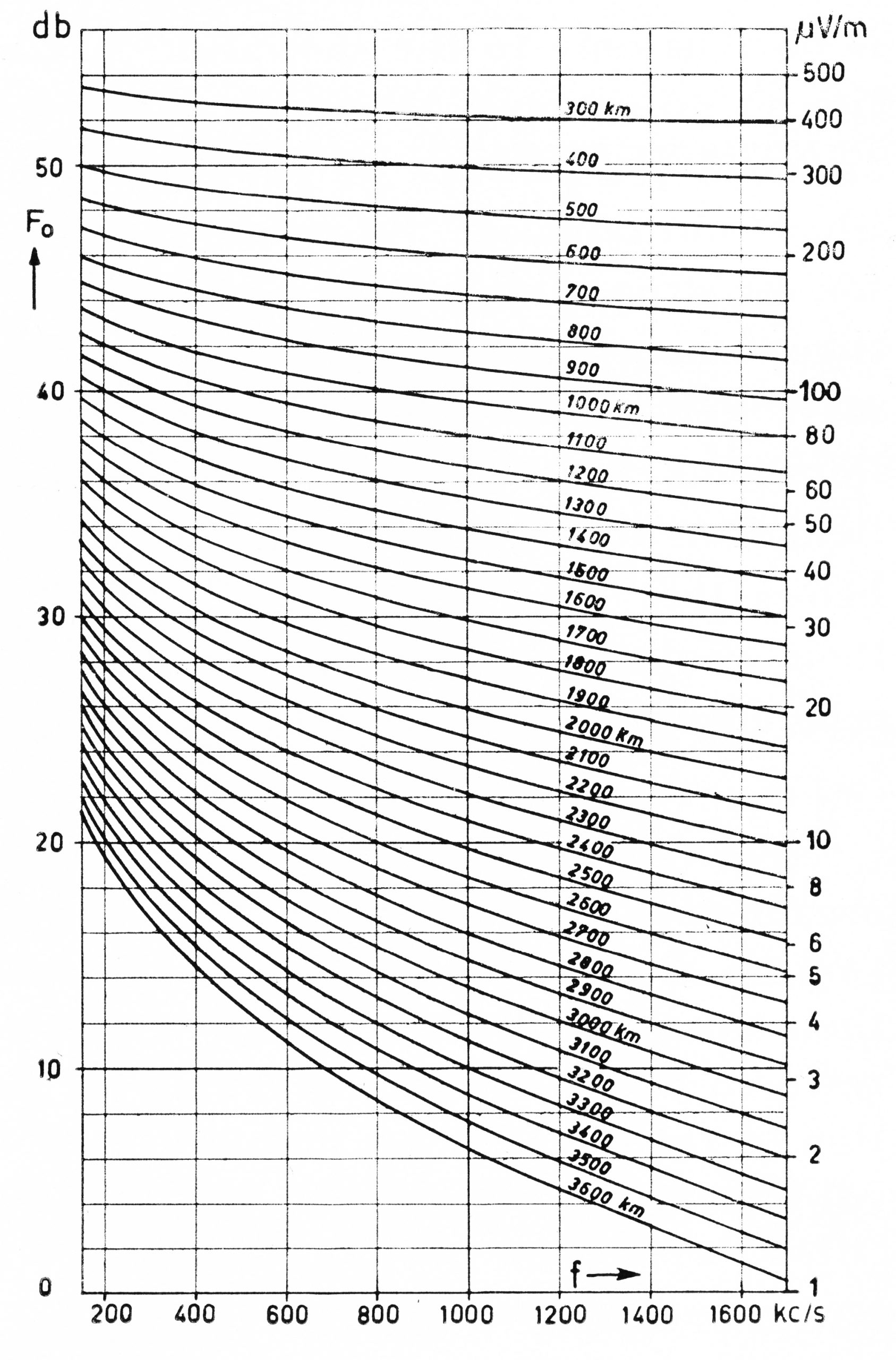

This is particularly true for long and medium waves, the “classical” broadcasting wavebands, those by means of which it took its first steps and which even today reach the largest number of listeners. Working Party B (Ionospheric propagation on kilometric, hectometric and metric (Band I) waves) has been studying this question since 1951. It has organised, with the aid of twenty-three receiving stations in fifteen European countries, systematic measuring campaigns, which made it possible to undertake numerous scientific studies, and finally to analyse the results of more than 45,000 hours of field strength recordings. These results have been condensed into a series of formulae and curves which make it possible to predict the value of the field strength under the most diverse conditions (E.B.U. Monograph Tech. 3081 “Ionospheric propagation on long and medium waves. Results of an investigation organised by the E.B.U.”).

These conclusions have been submitted to the C.C.I.R. and may form basic essential data for future frequency assignment conferences. Such conferences must however, also have available exact details of the quality of the indirectly-propagated signal — that which is reflected by the ionosphere and which is received at distances from the transmitter of the order of 1,000 kilometres. It is evident that a frequency assignment plan that takes into account this signal as a useful signal, will differ fundamentally from a plan that takes into account only the ground-wave service, the average range of which is about 100 kilometres. This is one of the subjects studied by Working Party A (Sound broadcasting on long and medium waves), which has organised observation campaigns by means of tape recordings of musical programmes made at varying distances from the transmitters under consideration. The degradation of these programmes by ionospheric phenomena may thus be judged subjectively by a certain number of listeners. It is hoped to draw conclusions therefrom through the analyses of the results obtained.

The E.B.U. curves for ionospheric propagation on 150, 200, 300, 500, 700, 1000 and 1500 kc/s.

The curves represent the annual median values of the hourly median values of the field strength as a function of the range, under stated conditions.

Metric and decimetric waves are used for television (Band I: 41 to 68 Mc/s – Band III: 162 to 230 Mc/s and Band IV/V: 470 to 960 Mc/s) and for frequency-modulated sound broadcasting (Band II: 87.5 to 104 Mc/s). These waves are little affected by the ionosphere with the exception, however, of those of Band I.

In this field, too, the ionosphere is responsible for high field strengths at very long distances; thus, it is sometimes possible to receive in Western Europe television pictures originating from stations in the U.S.S.R. Working Party B deals with this problem, and field-strength measuring campaigns have been organised.

However, VHF and UHF propagation is in the first instance influenced by the electrical properties of the troposphere. As with long and medium waves, the forecast of the tropospheric field strength on VHF and UHF is of great importance for broadcasting organisations and for the frequency-assignment conferences. Working Party K (Television and sound broadcasting on VHF and UHF) has undertaken the coordination of work carried out in this field in several European countries. The propagation curves at present in use are to a large extent the outcome of this coordination. This Working Party also deals with matters of propagation within the service area of transmitters. The study of the behaviour of UHF waves in large towns is in fact necessary to determine the power of transmitters, the situation and height of aerials and the like.

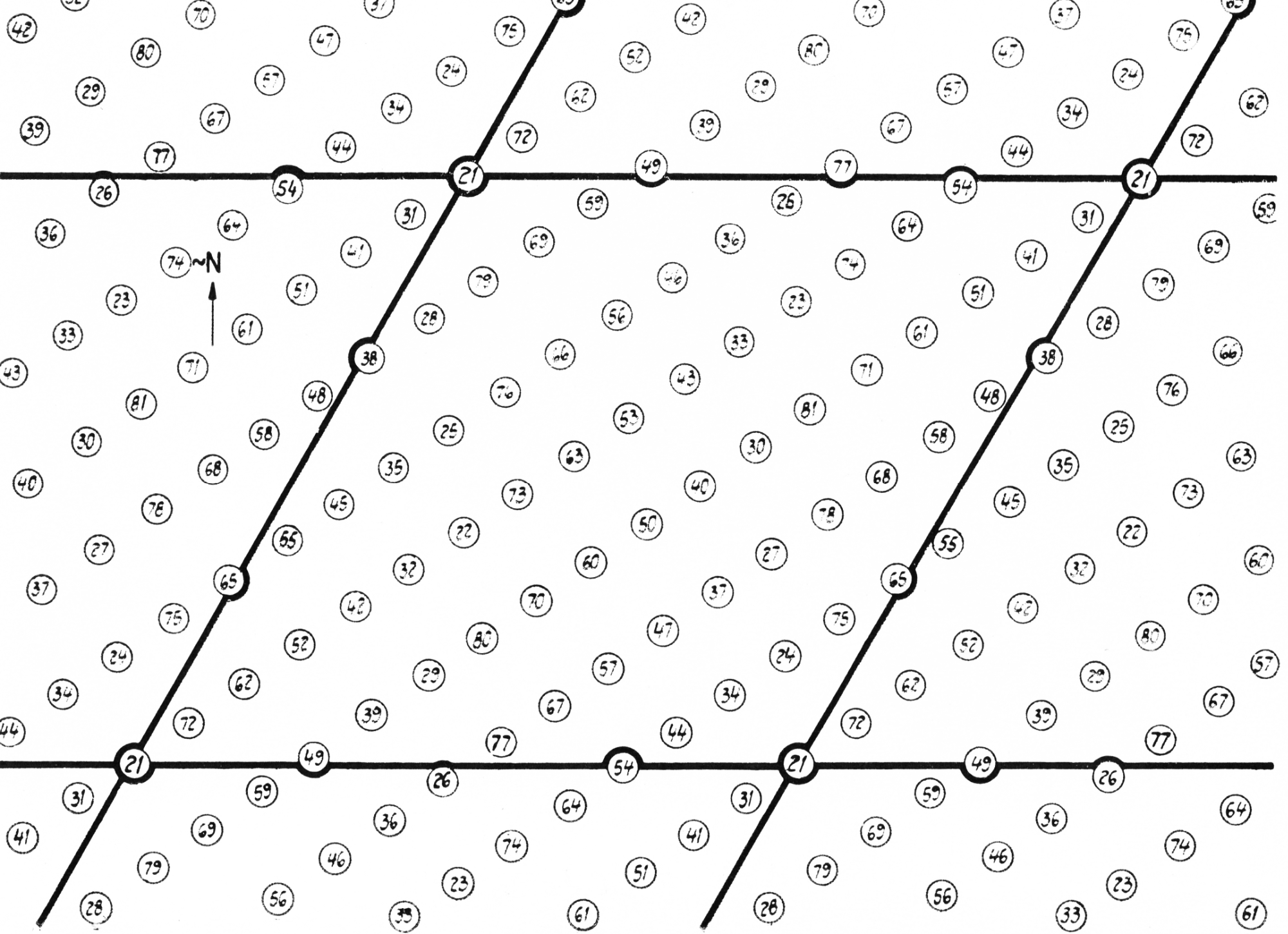

A theoretical lattice devised by the E.B.U. and used by the European VHF/UHF Broadcasting Conference, Stockholm, 1961.

RECEPTION PROTECTION

In addition to the characteristics of wave propagation, a frequency assignment conference must know the protection ratios between wanted and unwanted signals.

In sound broadcasting and in television, these ratios cannot be determined easily by direct measurements. It is the subjective impression of the disturbance felt by the listener or by the viewer that finally determines the value of this ratio. The corresponding experiments are usually of a fairly complex nature, and only broadcasting organisations with large laboratories are able to carry them out. It is therefore of interest to coordinate these experiments and to discuss their results on the international plane. This work is carried out within the framework of Working Party A on long and medium waves and within the framework of Working Party K on VHF and UHF.

This last-mentioned working party has also developed frequency-planning methods employing higher mathematics and requiring the use of electronic computers. A publication by the Technical Centre (E.B.U. Monograph Tech. 3080 “New methods of producing television frequency-assignment plans”) summarises this work. These methods were utilised at the European VHF/UHF Broadcasting Conference held in Stockholm in 1961. The diagram above represents a theoretical lattice established by Working Party K and which was used by this conference as a basis for the assignment of UHF. The photograph below shows the electronic computer used in Stockholm.

The next conference on long and medium waves will probably be prepared for in a similar way by Working Party A.

The BESK electronic computer utilised for verifying the plan established during the Stockholm Conference, 1961.

The protection of reception evidently does not rest with interference between transmitters. It also applies to electrical interference caused by industrial equipment, domestic appliances, fluorescent tubes and the like.

Counter-measures against interference on the international plane fall within the domain of the C.I.S.P.R., of which the E.B.U. is a member. The Technical Committee has consequently set up Working Party P (Collaboration with the C.I.S.P.R. and interference countermeasures) so as to be able efficiently to look after the interests of broadcasting and, in consequence, the interests of listeners and viewers, within the C.I.S.P.R.

The “presence” of broadcasting within this international organisation is certainly necessary, as most of the manufacturers of equipment likely to cause interference are represented.

PROBLEMS OF STANDARDISATION

When new facilities become available, the problems of standardisation that they pose on the international plane are always difficult to solve, since as often as not they involve in each country considerable economic interests.

Such was the case for monochrome television, for stereophonic broadcasting and for colour television. The technical organs of the E.B.U. in such a case offer the broadcasting organisations the possibility of putting forward their points of view. Are not in general the broadcasting organisations the first to suffer the inconveniences due to the absence of international standards?

Although it was not possible to adopt a single television system throughout Europe, the work of Working Party M (Long-distance television transmission) on standards converters, that is to say, equipment for converting television pictures having one number of lines to pictures of some other system, enabled the programme exchanges to become much more numerous. Moreover uninterrupted improvement in the quality of converted pictures has been noticed since 1954. Readers may compare the two photographs, taken in 1954 and 1959, of scenes televised near the Arc de Triomphe in Paris and photographed off the screen in Milano, after conversion from 819 to 625 lines.

a) 29th June, 1954

b) 8th January, 1959

The advance of Eurovision picture quality.

Both of these photographs are off picture monitor screens at Milan and represent scenes at approximately the same point of origin, near the Arc de Triomphe, Paris, the signal in both cases having been converted from 819 to 625 lines.

In the field of stereophonic broadcasting, the E.B.U. has gained a notable success. Working Party S (Stereophonic broadcasting) which was formed in 1959, has established a very comprehensive study programme. It has defined the minimum requirements needed for a satisfactory service and has coordinated the work of national laboratories that have undertaken the systematic study of all the systems proposed by industry throughout the world. The working party has reached very clear-cut conclusions that favour a single system, namely that adopted in the United States of America. These conclusions have been submitted to the C.C.I.R. and are likely to be used as basis in the establishment of world-wide standards for stereophonic broadcasting.

As regards colour television, the problem was much more complex. Working Party H made possible a comparison of points of view in 1955 and 1956, but of course the question was not then ripe for standardisation, and the working party ceased its activities in 1956. Needless to say, the E.B.U. will in due course help to find a solution.

The broadcasting organisations must study other technical innovations, matters that do not necessarily give listeners or viewers any new services. Thus, Working Party A, mentioned above, deals with methods of reducing the overcrowding of the long- and medium-wave spectrum (compatible single-sideband transmission or reduced bandwidth transmissions).

Working Party G (Recording of sound and pictures) has for years dealt with matters of magnetic and optical recording of sound and pictures. International standardisation in this field is of capital importance for the broadcasting organisations. In fact, in order to carry out programme exchanges, either on magnetic tape or on film, it is indispensable that these tapes or films can be utilised on the sound and vision tape equipment or in film-scanners of the organisation to which they have been sent. The conclusions of this working party have been submitted to the C.C.I.R., and the recommendations issued by that organisation are based on them.

OPERATIONAL QUESTIONS

Certain problems of operation, for example, those concerning Eurovision, interest the E.B.U. directly. For this purpose, the Technical Committee has set up Working Party L (International television relays), within which the representatives of the television organisations and the Administrations of the countries taking part in the Eurovision exchanges work in close and friendly cooperation. Working Party L having become rather numerous, it was necessary to form sub-groups with a limited number of participants in order to deal with certain particular problems.

The Code of Practice Sub-Group has prepared an operating handbook issued in English, French and German, which is constantly kept up to date and in which are summarised all the regulations and information necessary for the harmonious running of Eurovision operations.

The Sound Sub-Group deals with questions relating to the transmission of the sound signal and to the communication facilities. The Technical Centre has been charged with developing a standard programme-level indicator; such a device, which could later be used throughout the Eurovision network, will make it possible to overcome the difficulties due to the use of two types of programme-level indicators, namely, a peak programme meter and an integrating meter (VU-meter).

Working Party L has also developed standard commentator’s equipment. The generalisation of this equipment will enable commentators to find in each country in Europe equipment having the same control device. The photograph herewith shows one of these apparatus.

One of the commentary positions of the B.B.C. London Television Centre. The E.B.U. Commentators’ Unit can be seen on the table in front of the commentator.

The standardisation of “test signals” and “test lines” and of “test films” also proved to be necessary, and it is the object of work by Working Party M.

Certain problems that are not really of an international nature and to which different solutions may be found from one country to another, are nevertheless of great interest for broadcasting. It therefore seemed useful to compare the studies and work undertaken in this connection in the different countries. One of these problems is the introduction of automatic control into broadcasting.

Working Party D (Remotely- and automatically-controlled sound and television broadcasting stations) from 1951 to 1956 dealt with the problems posed by the installation of transmitters operated without or with a reduced staff. The comparison of the results obtained in the different countries proved to be very fruitful and has certainly contributed to the development of this form of operation in Europe.

This 600-kilowatt long-wave transmitter at Motala (Sweden) is remotely controlled and operates without supervision.

Finally, a number of problems relating to the daily operation of the transmitters, studios and sound and television broadcasting links, is dealt with by the E.B.U. in Technical Monographs either prepared by the Technical Centre or by a group of experts in the various countries. These monographs report on the experience gained. The subjects dealt with cover a very wide field:

- Problems of television concerning lighting, the installation of studios, transmitters in high mountains, the specifications for the construction of UHF transmitters, microwave links, the choice of site and of the type of mast or tower for supporting the aerials, standards converters, rebroadcasting stations, O.B. vehicles, the recording of pictures and the establishment of frequency assignment plans.

- Problems of sound broadcasting, concerning synchronised groups of transmitters, the introduction of frequency modulation on metric waves or the international exchange of magnetic tapes.

- Finally, more general problems, such as the notification and registration of frequencies, technical advice to listeners and viewers, measuring vehicles and monitoring stations, radio interference legislation and services, the introduction of transistors into equipment and safety measures for protecting the staff.

The E.B.U. Review, as has already been mentioned, also contributes to keeping the Members of the Union informed on subjects of general interest.

TRANSMISSION MONITORING

The monitoring of transmissions was one of the principal technical activities of the I.B.U. before the war, and its Technical Centre had been planned mainly with that task in view.

Since then, the quality of transmissions, especially as regards their frequency constancy, which is an important factor in reducing interference to a minimum, has continuously improved, thanks to the modernisation of the equipment, on the one hand, and to the construction of a large number of national monitoring stations, on the other hand.

Nevertheless, the Members of the E.B.U. deemed it essential to maintain an international monitoring centre. That is why the E.B.U. runs a receiving and measuring station, situated at Jurbise, near Mons, in the south of Belgium, which forms part of the Technical Centre. By means of equipment that is always being brought up to date, this station supervises continuously the long- and medium-wave spectrum and notifies E.B.U. Members of any changes.

The E.B.U.’s Receiving and Measuring Station at Jurbise-Masnuy (Belgium).

Thanks to a close collaboration between Jurbise and similar stations of Members and Administrations, an efficient and rapid means of information is available as well as — and this is still more important — objective data for the friendly settling of any difference that might arise between the Members of the Union or between them and other organisations.

This monitoring is done by means of frequency measurements and, if necessary, also by field strength measurements. It goes without saying, and this happens often, that the Jurbise station also undertakes measurements at the special request of Members.

In the field of short waves, it is evidently no longer possible to monitor at Jurbise the whole of the frequency bands, but monitoring is nevertheless carried out thanks to the collaboration of a large number of monitoring stations situated not only in Europe, but also in America, Africa and Australia.

The short range of VHF and UHF waves used for television and frequency modulation makes it impossible to receive them beyond a certain distance. The Jurbise station has also been equipped with a mobile measuring unit that may be put at the disposal of E.B.U. Members.

The Technical Centre regularly publishes Reports, Lists and Maps describing the situation in all the wavebands utilised in Europe for sound broadcasting and for television, and in particular, the characteristics of the stations operating in these bands. This information is based on observations made at Jurbise and at the national receiving centres, as well as on information received from Members of the Union.

Activities in the Legal field

Activities in the

Legal field

The raison d’etre and the justification for the E.B.U. is the existence of interests that are common to its Members, and it follows that common interests are best furthered by joint action. This concept of solidarity runs through all the legal activities of the E.B.U., whether undertaken by its Legal Committee or by its permanent staff. The explanation for this is obvious. Programme production and programme exchanges between organisations in different countries involve rights that are usually controlled on an international basis and can only be properly secured when this special situation is taken into account. For many decades copyright has been governed by multilateral Conventions, and the same is now true of the rights of performers and those of the phonographic industry. The music publishers have also banded together in an international association to confront the users of the scores they publish. Copyright works, the performances of musicians, singers and actors, commercial records and editions of operas, musical comedies and symphonic music are all the raw material of radio and television, without which these services could not exist. In its turn television has further complicated the lawyer s task. Films, works of visual art and “shows” of all kinds are consumed by television in vast quantities every day, whereas sound radio was either unable to give them at all or could only transmit the sound component. In addition to that, the development of certain new technical devices made it necessary to protect the broadcasts themselves against unauthorised appropriation by outsiders. The work of the legal departments of broadcasting organisations has therefore been growing steadily in recent years, and as these problems attain international dimensions they likewise increase the activities of the Legal Committee and its permanent secretariat, its study groups and its various negotiating delegations. The following brief account will undoubtedly bear out this statement.

INTERNATIONAL TREATIES

Members of E.B.U. belong to countries which are parties either to the Berne Convention or to the Universal Copyright Convention or to both, and accordingly it is of the utmost importance for them to be familiar with the exact operation of these international instruments and to keep a close eye on any possible revisions. The Universal Copyright Convention was only finalised in 1952 and has not been in effect long enough to warrant holding a revision conference. On the other hand the Berne Convention, the corner-stone of international copyright legislation in Europe, is already the subject of intensive work with a view to the Revision Conference to be held in Sweden in 1965. The E.B.U. Legal Committee is now studying the points on which a revision might be desirable and is preparing the basis for a common policy on the part of member organisations which will have to make representations to their governments in due course to ensure that the Convention is not revised in a manner prejudicial to their interests.

Towards the end of 1961 another Convention came into being. This Convention, which has direct and far-reaching implications for the broadcasting industry, is the instrument dealing with international protection for what are known as “neighbouring rights”, these being the rights of performers, record manufacturers and broadcasting organisations themselves. From its inception in 1950 the Legal Committee occupied itself with this problem, in the belief that a Convention on “neighbouring rights” would be concluded sooner or later, and played a very active and important part during the ten years that the Convention was on the stocks. The E.B.U. was present at every stage of the preliminary deliberations, was a member of all the Committees of Experts and was able to play a decisive role in the final drafting of the treaty through its contacts in the national delegations to the Diplomatic Conference. It may confidently be said that without this patient work over the years the Convention might have granted rights that would have had extremely serious repercussions on the operations of the broadcasting organisations.

At the specifically European level the Legal Committee plays a prominent part in the Intergovernmental Legal Committee on Broadcasting and Television functioning under the auspices of the Council of Europe. It is largely due to this fact that two European agreements have been concluded on the subject of television, both of which were modelled on the doctrine laid down in the E.B.U. Legal Committee. The first of these instruments, which six States have ratified to date, facilitates exchanges of television programmes by means of films and removes legal obstacles which, in the absence of such a treaty, might restrict films to exhibition in the country of origin alone. The second instrument to date ratified by four States and in the process of ratification by others, makes provision for domestic and international protection for television broadcasts against various forms of plagiarism, particularly the unauthorised reproduction of whole sequences or of still photographs off the screen, unauthorised wire diffusion and other forms of unlawful appropriation.

At the instance of the Legal Committee, the Council of Europe has at present under consideration a draft European agreement designed to put a stop to the activities of broadcasting stations operating contrary to international law on board vessels or aircraft in international waters or in international airspace.

France signs the “European Agreement concerning Programme Exchanges by means of Television Films” at a meeting of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, 1958. In this view of the ceremony, Mr. Lenoble, President of the E.B.U. Legal Committee, is seen standing behind Mr. Couve de Murville, Minister of Foreign Affairs, France.

DOMESTIC LEGISLATION

At the national level the Legal Committee and its Secretary, the E.B.U. Legal Adviser, have frequently had occasion to consider the legislation in preparation in the various countries to which member organisations belong. Opinions have been expressed and advice given to ensure that the enactment in question, on such subjects as copyright, “neighbouring rights”, the organisation of broadcasting services, libel, etc., is as favourable as possible to the interests that the E.B.U. stands for. The Legal Adviser has had a hand in the framing of domestic Bills and continues to do so; this co-operation is beneficial to all the Members because the subjects in question — copyright and broadcasting — overstep national frontiers. This is also a form of technical assistance to under-developed countries, because this particular type of legal aid has been granted to several African countries at the request of the local broadcasting organisation belonging to the E.B.U.

The Legal Committee has also set up a special Working Party with the task of framing a model enactment for the new African countries, the purpose of which is to reconcile the legitimate interests of the various rightholders with the nation-wide needs of the broadcasting organisation.

Another Working Party is currently engaged in preparing a model domestic enactment on the protection of “neighbouring rights”, to which reference has been made above. The work of this Working Party will undoubtedly be of tangible benefit to many organisations.

INTERNATIONAL CONTRACTS

The proprietors of the rights which sound and television broadcasting require and use in their operations have joined forces in international associations, as mentioned above. It is therefore the obvious course for the E.B.U. to get into touch with these associations and endeavour in agreement with them to standardise the use of the rights they control. In this way several international standard contracts have been negotiated by the Legal Committee or by delegations it has appointed, and these contracts are used as the basis for domestic contracts and are applied at the present time by a large number of E.B.U. member organisations.

The earliest of these contracts was a contract signed with the organisation controlling a very wide international catalogue of musical works, with or without words, in respect of the right of reproduction. With such a tremendous growth in the magnetic recording of sounds and images, an international standard contract with a body authorised to license the recording of copyright works was an absolute necessity. The standard contract came into force in 1953 and, with successive revisions, still governs the recording of a world-wide repertoire of intellectual works in many countries where the E.B.U. has a Member.

Another standard contract was signed with the phonographic industry to determine in a uniform and equitable manner the general terms on which broadcasting organisations can use commercial records. The importance of this contract will increase as the international Convention on “neighbouring rights” might induce various countries to give the phonographic industry either a property right or a right to remuneration in respect of the use of records for broadcasting purposes.

Two other contracts with the music publishers which govern the rental of scores for recording and broadcasting purposes are widely applied at the domestic level. It is generally known that nowadays a music publisher does not print the works he controls or put them on public sale except in the form of piano arrangements or of excerpts, and that he has only a very small number of copies made of the scores required for full-dress performances. When a broadcasting organisation wishes to make a broadcast of such a work it has to hire these “materials” or scores. The Legal Committee had to work out very complicated clauses in the two contracts to cover all the possible situations that may arise in both sound radio and television. Discussions are now in progress with regard to the revision of these contracts.

Another international contract which the E.B.U. may sign once it has been finalised by the Legal Committee will dispose of certain problems raised by the international performers’ federations with regard to international exchanges of programmes in sound radio. These are mainly matters of a trade-union nature, and the agreement that may be signed will have all the features of an international collective agreement. It is hoped that it will have the effect of pacifying the unions’ apprehensions about what they consider to be the over-frequent use of recorded instead of live performances.

NATIONAL CONTRACTS

The standard contracts to which reference has been made above are used as pro-formas for the conclusion of national contracts. When the latter are being negotiated and when other contracts are being drawn up or when disputes arise at the national level between a member organisation and one of the bodies with which it has a contract, the E.B.U. Legal Department is often called in. Many national contracts have been negotiated or revised with the Department’s assistance. On the basis of the periodical surveys it makes, the Legal Department can inform Members at any time how much is paid in other countries for the acquisition of a particular type of right, and what contractual devices are used to effect a fair settlement of a given problem. Legal assistance in the contractual negotiations of member organisations is one of the E.B.U. Legal Adviser’s regular duties.

EUROVISION

Eurovision has brought with it a host of questions that the Legal Committee has had to deal with urgently. It has been necessary, for instance, to overhaul the standard contracts which originally made no provision for this form of international co-operation, and to conclude others.

As far back as 1957 an international collective agreement was signed with the three international performers’ federations to determine, among other things, the size of the supplements which performers engaged at a fee would receive for a Eurovision broadcast, depending on the number of relaying organisations. This Convention, which is limited to the Members situated in the European Broadcasting Area, does not apply to intercontinental transmissions of professional performances via satellites.

It was found necessary to put the dealings with international newsfilm agencies on a firm contractual basis in order to settle the problems arising out of the contracts between these agencies and Eurovision. On the one hand, these agencies stand to gain by having their news items flashed over the Eurovision network, more speedily than by other means of transport, and on the other hand they would like to take from Eurovision certain news sequences that they have not obtained from their own correspondents. A standard contract and a set of rules laid down by the Legal Committee now govern these matters.

The increasing frequency with which sporting events are given on Eurovision has made it necessary to work out standard clauses for insertion in contracts for the purchase of the television rights in such events. The Legal Committee has had to consider several cases in this particular field, and it is the standing practice for the Legal Adviser of the E.B.U. to take part in negotiations relating to sporting events of international importance such as the Olympic Games or the various World Championships.

The desire of certain outside interests to forward closed-circuit transmissions over the Eurovision network has led the Legal Committee to make specific recommendations, and it has also had to consider the terms and conditions in contracts for the rental of circuits to be included in the future permanent network, in order that these contracts should correspond exactly to the requirements of the E.B.U. and of its Members.

No sooner have these problems been solved at the Eurovision level than they crop up again, with others, at the world-wide level on account of intercontinental transmissions via artificial earth satellites, now all accomplished fact. The Legal Committee will have to study the conditions to which such transmissions must conform in order to remain within the law not only in the originating country but also in the receiving country or countries. This is a problem of considerable magnitude, and so are the claims already being pressed by some of the contractual partners of the organisations likely to make such transmissions. In close cooperation with the legal departments of the member organisations in the American continent, the E.B.U. Legal Committee hopes to be able to resolve the problems that now lie before it.

COOPERATION BETWEEN THE COMMITTEE AND OTHER ORGANISATIONS

It would not have been possible to do everything that the Legal Committee has hitherto accomplished without frequent cooperation with other international bodies. Foremost among them are the intergovernmental agencies whose meetings are attended by the E.B.U., which is authorised to take part in the debates and expound its views. These are the various committees of the International Union for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, Unesco, the Council of Europe and the International Labour Organisation. At the non-governmental level the E.B.U., represented by the Legal Committee, is in regular touch with the international professional and trade organisations whose activities touch on those of the E.B.U. Sometimes standing joint committees are set up as a forum for periodic meetings, discussions and negotiations. Such committees have been set up with the International Confederation of Authors’ and Composers’ Societies (C.I.S.A.C.), the International Bureau of Mechanical Recording, the music publishers and the phonographic industry. Co-operation has also been established with the International Federation of Film Producers whose interests, on certain matters at least, run parallel with those of the E.B.U. The Legal Committee has always pursued a policy of being present at meetings, believing that the E.B.U. should be represented wherever the interests of its Members are at stake.

INTERNAL ORGANISATION OF THE COMMITTEE

The increasing number of participants at sessions of the Legal Committee is the best sign of the interest aroused by its activities. It also is significant that the Associate Members from other continents are attending sessions more and more frequently. The Bureau of the Legal Committee may be consulted by the permanent E.B.U. staff in urgent cases and it sometimes happens that the Committee entrusts it with certain tasks that have to be performed in the period between two sessions. The Chairman of the Committee is responsible for drawing up its agenda, for reporting on its sessions to the Administrative Council and the General Assembly, and for seeing to it that the decisions of these bodies are carried out.

The increasing range of its responsibilities may lead the Committee to decentralise more of its tasks, to set up more working parties than in the past and to give them more specialised terms of reference than it has hitherto done. This is the way in which it can probably best and most speedily live up to the expectations of the member organisations.

Eurovision

Eurovision

What is Eurovision?

The achievement of a community…

The European Television Community, usually abbreviated to “Eurovision”, represents an arrangement between the television services in the north, west and south of Europe, which decided to integrate their facilities in order to develop the international exchange of television programmes. The television services in question are all exploited by Members of the E.B.U., the permanent establishments of which undertake the coordination of these exchanges both on the technical and on the programme planes.

Many readers who are unfamiliar with the situation of television in Europe may wonder why it was so difficult in the beginning to organise these international television relays. The reason was a simple one: the lack of standardisation.

Towards 1953, when the question of the possibilities of exchanging television programmes began to be raised seriously, the television services in operation in Europe were in very different stages of development. In some countries, they were already serving virtually the whole of the national territory, whereas in others only the capital was served. Moreover, the services had often very different situations from the organisational point of view — some being Departments of State, whereas others were chartered corporations and others private enterprises. Again, in certain countries the television service owned and exploited its own studio centres, the outside-broadcast facilities, microwave or cable network and transmitting stations, whereas in other countries some or all of these facilities were provided by the Telecommunication Administration. To these complications had to be added various difficulties caused by the diversity of language. In addition, there were the differences in the technical transmission characteristics — systems using 405, 625 and 819 lines per picture were in use, but fortunately all the systems had a field frequency of 50 per second. At the beginning, too, there were significant differences in the technical equipment used for the radiolink networks, which made it difficult to connect them in tandem.

It is therefore not to be wondered at that it was far from easy to establish a Community in such unfavourable circumstances. What is perhaps more surprising is that it was not established with that precise aim in view and that it represented in no way a deliberate objective of the governments of the countries concerned. The European Television Community in fact developed quite gradually, and it began indeed in a very modest fashion.

It was rather a concourse of practical considerations, notably the wish of the programme planners to provide their audiences with live programmes originating in foreign countries, that gave rise to the first experiments, that excited all those who took part in them.

This installation at La Dôle (Switzerland) near the Franco-Swiss frontier, converts 819-line television signals to the 625-line standard, and vice-versa.

It was not difficult in effect — once the first exchanges had been effected — to persuade the various European television services of the benefits that they would obtain by linking their networks to the Eurovision Network, thereby assuring themselves of a supply of a wide variety of programmes, which they might, for technical or financial reasons, find it difficult to obtain otherwise. It should be mentioned that every television service established in Western Europe has joined the Community, as soon as it became technically possible to set up the necessary links.

However, the increase in the number of connected services posed the problem of coordinating the exchanges, on the international plane. As all the television services in the Community belonged to Members of the E.B.U., it was natural that they entrusted the task to the Union. It is true that at the beginning, the Union had none of the material facilities needed to undertake the task; it had neither the budget, nor the staff nor the equipment. Thanks to the help of the Members, which soon provided the money, the buildings, the equipment and the staff, Eurovision gradually developed.

…of great complexity

The problems that had to be solved, before Eurovision could function satisfactorily were rather formidable. First of all, it was necessary that in each participating country there should exist an adequate network of radio or cable links. This, of course, is a national problem inherent in the normal development of the television service. Then it was necessary to join these national networks together, but on different sides of the frontiers there are often different television standards, as already mentioned above. France, the French-speaking part of Belgium, Luxembourg and Monaco have pictures composed of 819 lines, the United Kingdom and part of Ireland have 405 lines, while the rest of Europe uses 625-line systems. Television pictures originating, say, in the United Kingdom cannot be reproduced directly on French receivers. The signals have first to be “converted”, that is to say, changed from 405 to 819 lines. Standards conversion, of which this is one example, is one of the important problems in planning Eurovision operations.